Using tumor antigen-loaded monocyte-derived DCs for therapeutic vaccination is a strategy that has been well explored, but with mixed clinical results. While this strategy can be effective, it is limited by the requirement for accessible tumor samples or known tumor antigens, as well as by the antigen loading process itself. To overcome these limitations and create a better DC-based vaccine, Ghasemi et al. developed a platform based on DC progenitors (DCPs) engineered to produce IL-12 and FLT3L, which generate cDC1 in vivo and induce antitumor immunity.

To begin, Ghasemi et al. developed a protocol for the ex vivo production of common DC progenitor (CDP)-like cells, termed DCPs, from murine bone marrow cells. Upon systemic administration into mice (without prior myeloablation), DCPs efficiently engrafted and reconstituted cDC1 and, to a lesser extent, cDC2, outperforming monocyte-derived DCs or cDC1s. Similar observations were made in tumor-bearing mice, with DCPs efficiently engrafting in tumors.

Evaluating ways to enhance DCPs, the researchers used lentiviral vectors to engineer DCPs to express FLT3L, which is essential for cDC1 induction and expansion. In mice, DCP-FLT3L effectively expanded endogenous cDCs in both tumors and spleens, and increased CD8+ and CD4+ effector T cells compared to control DCPs. The team also engineered DCPs to express IL-12, which they had identified in a cytokine panel for its capacity to enhance cDC1-like cell differentiation and costimulatory capacity.

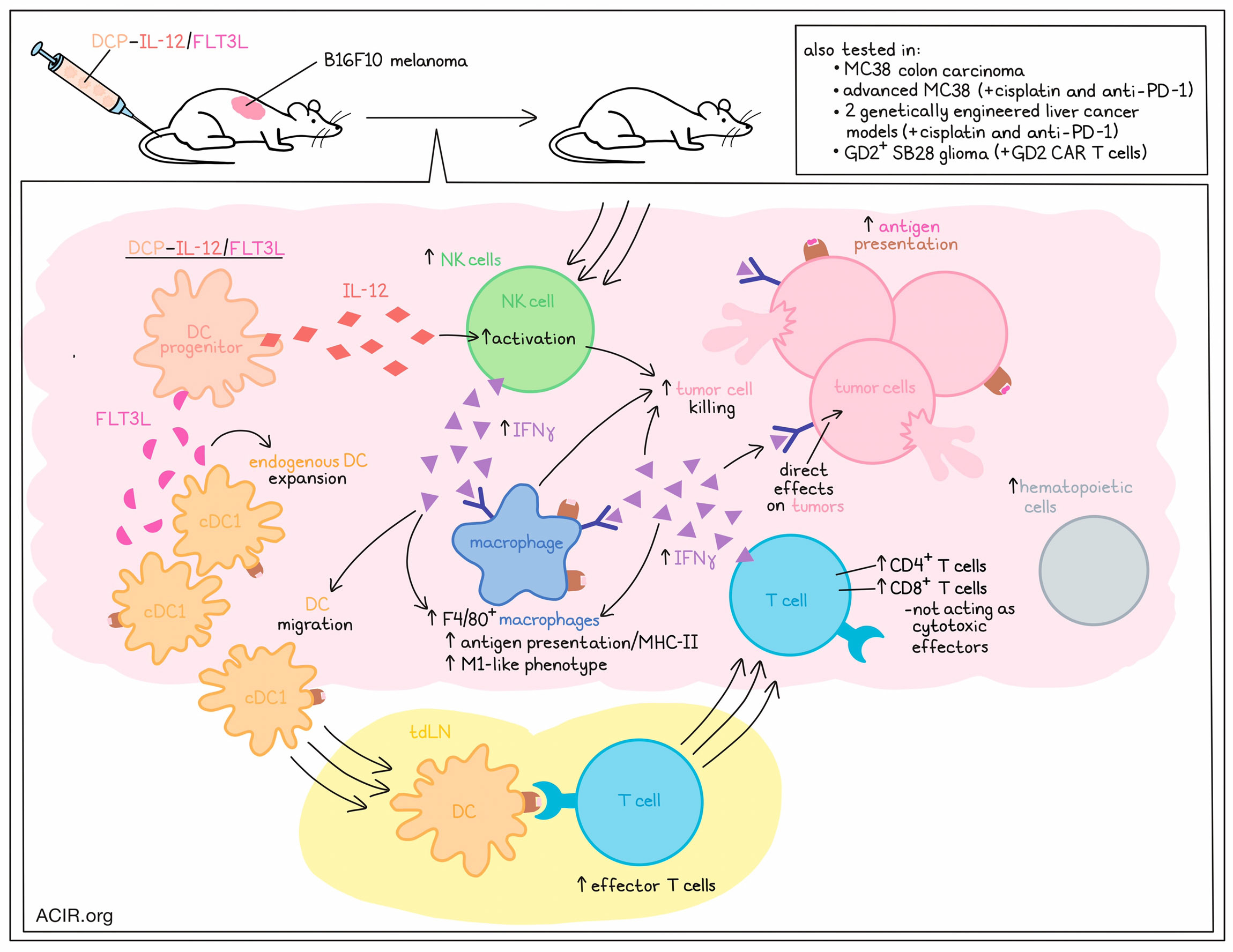

In a B16F10 melanoma mouse model, DCP-FLT3L had little effect, but DCP-IL-12 slowed tumor growth, and the combination of DCP-IL-12 and DCP-FLT3L cells achieved tumor stabilization. Further evaluation revealed that IL-12 and FLTL3 synergized to increase the infiltration of hematopoietic cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells into tumors; increase the proportions of activated T cells expressing IFNγ in tumors; and increase the relative abundance of effector CD4+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. DCP-IL-12, both alone and in the combination treatment, also contributed to increased TAM expression of MHC-II, indicating a shift towards a more immunostimulatory M1-like phenotype. In mice treated with the DCP-IL-12/FLT3L combination, the researchers noted increased activation of various immune response pathways, including antigen presentation and IFNγ/type-I IFN signaling pathways in both cancer and myeloid cells. Similar results were observed in an MC38 colon carcinoma model, which is heavily infiltrated by immunosuppressive TAMs. Further, similar results were observed when DCPs were engineered to express both IL-12 and FLT3L in the same cells.

To better understand the effects of DCP-IL-12/FLT3L treatment on the immune microenvironment, and how it mediates enhanced antitumor immunity, Ghasemi et al. evaluated tumor samples at an early time point after DCP transfer. At this time point, treatment had only slightly increased hematopoietic and CD8+ T cell infiltrates, but had strongly increased activated NK cells, likely due to the increased IL-12. Interestingly, FLT3L appeared to increase cDCs within tumors compared to tdLNs, while DCP-IL-12 or DCP-IL-12/FLT3L reduced cDCs in tumors, while augmenting them in tdLNs, where effector T cells were also increased. These results suggested that the expression of FLT3L likely promotes an initial expansion of endogenous cDCs in tumors, while IL-12 expression recruits NK cells that express IFNγ, driving cDC migration to the tdLN and subsequent priming of effector T cells.

Interestingly, the researchers found that endogenous cDC1 were required for effective antitumor immunity in response to DCP-IL-12/FLT3L, but CD8+ T cells were not. In Rag1−/− mice (lacking T and B cells) bearing B16F10 melanomas, the researchers observed a strong increase in the proportion of activated PD-1+ NK cells. In neutralization studies, though, the simultaneous elimination of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells and NK1.1+ NK cells only moderately hindered treatment efficacy. Only the neutralization of IFNγ fully abrogated the effects of treatment. Interestingly, DCP-IL-12/FLT3L increased F4/80+ TAMs, dependent on IFNγ and CSF1R, and the depletion of TAMs moderately limited the efficacy of DCP-IL-12/FLT3L, suggesting that they play an antitumor role in this treatment setting. Further, IFNγR expression on tumor cells was required for antitumor efficacy. Together, these results suggested that DCP-IL-12/FLT3L mediates antitumor efficacy by increasing IFNγ production in the TME, which remodels TAMs and exerts direct effects on tumor cells.

To study cytokine-armed DCPs in more advanced tumors, the researchers tested them in models of MC38 in combination with cisplatin pre-treatment and anti-PD-1. In this setting, only the full combination treatment was sufficient to stabilize or regress tumors. The addition of DCP-IL-12/FLT3L contributed to increased tumor infiltration and immune activation and reduced immune exhaustion, independent of anti-PD-1. The TCR repertoire also trended towards increased diversity in this model, suggesting the expansion of tumor antigen-specific T cell populations.

Next, the researchers tested their cytokine-armed DCPs in two genetically engineered liver cancer models, established through the systemic injection of cancer-causing plasmids. In the first model, which has an immunosuppressive and nearly immune-desert TME, treatment with DCP-IL-12/FLT3L (on top of cisplatin and anti-PD-1) reduced the numbers of macroscopic tumors and large tumors and extended survival, with 4/11 mice tumor-free at day 23. In the second model, which develops fewer tumors, harbors dysfunctional DCs, and is resistant to immune checkpoint blockade, DCP-IL-12/FLT3L (on top of cisplatin and anti-PD-1) induced 100% survival, with 5/6 mice free of macroscopic tumors at day 21. In both models, DCP-IL-12/FLT3L increased T cell infiltration and the proportions of activated (IFNγ+) and effector (CD44+CD62L-) T cells in tumors.

In a final mouse model, the researchers tested DCP-IL-12/FLT3L in combination with GD2-targeted CAR T cells against GD2+ SB28 glioma, which is immunologically silent and unresponsive to checkpoint blockade. Here, the combination DCP-IL12/FLT3L treatment improved survival over either monotherapy, inducing complete, long-lasting tumor regressions in 4/5 mice.

Moving towards clinical relevancy, the researchers developed a protocol in which they could derive human DCPs from human CD34+ HSPCs, obtained from either cord blood or mobilized peripheral blood. The resulting DCPs, defined as Lin-CD34+CD115+ cells, could be efficiently transduced with a lentiviral vector and could differentiate into various APCs, including monocytes, cDC1, cDC2, and immature DCs. These cells were capable of direct antigen presentation, cross-presentation, and cross-dressing, each of which could activate antigen-specific T cells more efficiently than monocyte-derived DCs.

Overall, Ghasemi et al. showed that therapeutic administration of DCP-IL-12/FLT3L, without exogenous antigen, induced strong antitumor immune responses in a variety of murine tumor models, and in combination with existing chemo- and immunotherapies. These responses were associated with increased NK and T cell activation and M1-like macrophage programming, and were dependent on endogenous cDC1 and IFNγ, but not cytotoxic T cell responses. This strategy provides a promising alternative to vaccination with tumor antigen-loaded DCs.

Write-up and image by Lauren Hitchings

Meet the researcher

This week, lead author Michele de Palma answered our questions.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

One interesting, and perhaps unexpected, observation was that cytokine-armed DCPs functioned independently of CD8+ T cells, which are often required for antitumor immunity in mouse tumor models. Indeed, the treatment achieved tumor control also in mice that genetically lack mature T cells, or in which T cells were experimentally eliminated. These provocative findings argue against the notion that tumor response to cytokine-armed DCPs involves antigen presentation and subsequent killing of cancer cells by T cells. The ability of engineered DCPs to broadly reprogram the tumor microenvironment, for example, through the activation of natural killer (NK) cells and anti-tumoral (M1-like) macrophages, or via inhibition of angiogenesis, may explain this result. In particular, our results suggest that interferon-γ (IFNγ) signaling in multiple cell types, including cancer cells, plays an essential role in governing the antitumor response.

What is the outlook?

Our results further indicate that DCPs can function in an antigen- and tumor-agnostic fashion, meaning that, in principle, they can be applicable to a variety of cancer types, independently of their antigenic makeup. We could generate DCP-like cells from hematopoietic progenitors isolated from the human blood, potentially paving the way to clinical applications of DCP-based therapies.

What was the coolest thing you’ve learned (about) recently outside of work?

I am a passionate, semi-professional entomologist. In my spare time I study the taxonomy of the flower chafers (Cetoniinae), a group of scarab beetles distributed worldwide that have wonderful shapes and colors and visit flowers and ripe fruit. Probably one the major highlights of my entomological endeavors in the last few months has been the discovery and description of a new species of flower beetle – a cyan-colored large insect – from the remote forests of Myanmar, which I named Agestrata fortii.