In the clinic, anti-CTLA-4 induces more durable responses than anti-PD-1. In recent research, Mok et al. investigated possible mechanisms underlying this durability by using a variety of mouse tumor and vaccine models. They found that anti-CTLA-4 induced stronger memory responses than anti-PD-1 by preserving CD8+ T cells with high levels of TCF-1 and low levels of TOX (less differentiated), with help from CD4+ T cells. Anti-PD-1, on the other hand, supported CD8+ T cells with lower levels of TCF-1 and higher levels of TOX (more differentiated), which showed reduced memory responses. Their results were recently published in PNAS.

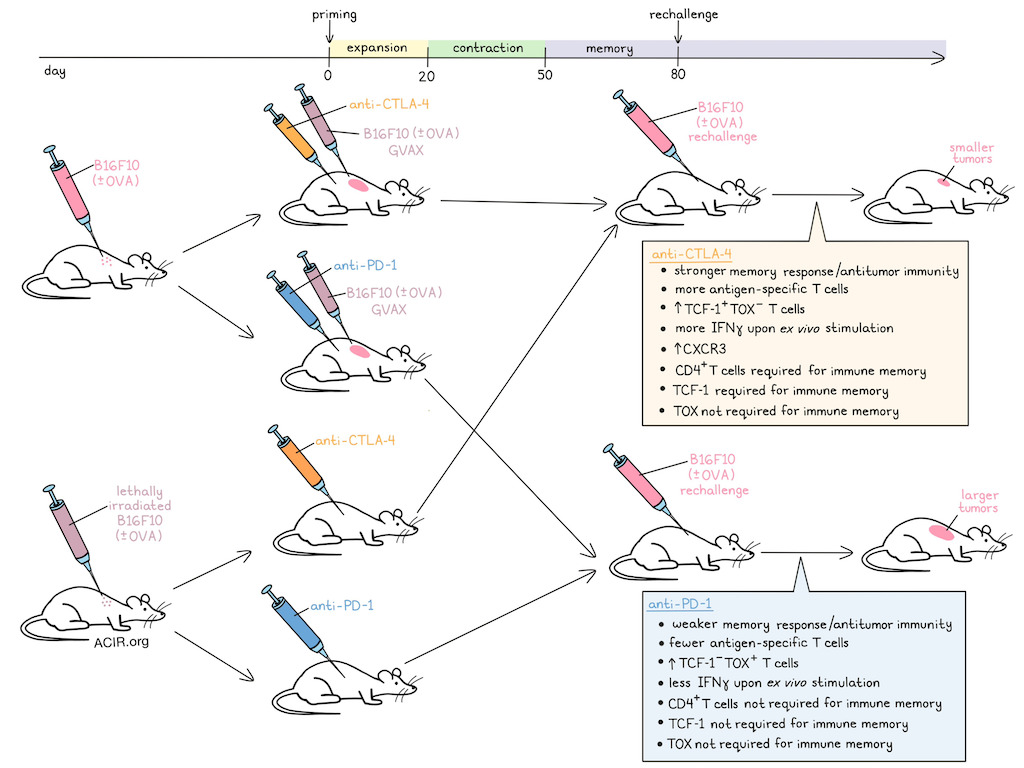

Mok et al. began by using a B16F10 tumor model, against which both anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 showed similar antitumor efficacy, but neither effectively cleared tumors as monotherapies. To study memory responses, anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 were each combined with vaccines consisting of lethally irradiated B16F10 expressing GM-CSF (B16F10-GVAX). This induced tumor clearance in 80% of mice for each treatment, allowing for rechallenge studies. Upon rechallenge at day 80, mice that had received anti-CTLA-4 had consistently smaller tumors than mice that had received anti-PD-1, suggesting stronger memory responses.

To eliminate the possibility that memory responses could be affected by chronic antigen stimulation due to the persistence of micrometastases in mice that had cleared their primary tumors, the researchers implanted mice with lethally irradiated B16F10 (instead of live cells) to allow for short-term antigen exposure, without the possibility of chronic antigen stimulation (vaccine model). While the vaccine alone did not support the formation of memory responses, the addition of anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1 induced immune memory, with anti-CTLA-4-treated mice developing smaller tumors upon rechallenge than anti-PD-1-treated mice. Similar results were observed with the murine 3LL lung cancer cell line. When mice were primed with one tumor line and rechallenged with another, no memory developed, suggesting that responses were antigen-specific.

Investigating possible factors that could account for the differences in memory responses between anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1, Mok et al. investigated delaying treatment, as CTLA-4 expression peaks earlier than PD-1 expression following vaccination. However, delaying treatment compromised memory generation for anti-CTLA-4 and had no impact on anti-PD-1 therapy. Extending treatment had no effect on either treatment group. Treg depletion was also tested by evaluating various clones of each antibody, including clones of anti-CTLA-4 that do and do not deplete Tregs. This showed that while Treg depletion enhanced immune memory, it did not entirely account for the improved memory observed with anti-CTLA-4 over anti-PD-1. When anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 were combined, memory responses were better than those of anti-PD-1, but similar to those of anti-CTLA-4, suggesting that memory in the combination treatment was mainly driven by anti-CTLA-4.

Next, the team used their vaccine model to evaluate the contributions of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells by selectively depleting one or the other during treatment with anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1. These populations were then allowed to recover, and mice were rechallenged at day 80. This revealed that when CD8+ T cells were depleted during priming, memory responses were weaker in both anti-CTLA-4- and anti-PD-1-treated groups. However, when CD4+ T cells were depleted during priming, the memory responses of anti-CTLA-4 were completely abrogated, while the memory responses of anti-PD-1 were unaffected. These results suggest that immune memory in both treatments is dependent on CD8+ T cells, but only anti-CTLA-4-induced immune memory is dependent on CD4+ T cells.

To track the kinetics of antigen-specific immune responses, Mok et al. implanted mice with an OVA-expressing B16F10 model, and treated them with a combination of lethally irradiated B16F10-OVA plus anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1 to mediate tumor clearance in 60% of mice in each treatment group, which were then rechallenged at day 80. Using OVA peptide-specific tetramers, the researchers showed that anti-CTLA-4 treatment led to a higher frequency of OVA-specific T cells upon rechallenge than anti-PD-1. To eliminate the potential effects of chronic antigen exposure, they again used an OVA peptide vaccine alone (no implanted live tumor cells), and saw similar results. They also saw similar results when rechallenging with the peptide vaccine instead of tumor cells, including over successive peptide vaccine rechallenges 80 days apart.

Based on the frequency of OVA-specific T cells in both models, day 0 to 20 was defined as the priming/expansion phase, day 20 to 50 as the contraction phase, and day 50+ as the memory phase. Antigen-specific T cells were similar between anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 on day 20 (representing peak T cell expansion) and during the memory phase across peripheral blood, bone marrow, and spleens, suggesting that differences in memory responses are likely due to qualitative, rather than quantitative differences in antigen-specific T cells.

Turning their attention towards phenotypic differences in T cells, the researchers evaluated expression of various markers associated with differentiation and exhaustion. Expression levels of Eomes and PD-1 (representing activation) were comparable between treatments, as were expression levels of inhibitory molecules. However, when equal numbers of antigen-specific memory T cells from each treatment group were transferred into mice, and those mice were challenged with B16F10-OVA, the cells transferred from anti-CTLA-4-treated mice showed superior antitumor immunity. They also more frequently expressed IFNγ upon ex vivo stimulation. Additionally, anti-CTLA-4 treatment preserved higher frequencies of TOX-TCF-1+ and CXCR3+Ly108- T cells and resulted in higher expression of CXCR3, while anti-PD-1 supported more TCF-1-TOX+ cells. Evaluating the roles of TCF-1 and TOX, the researchers generated mice in which Tcf7 or Tox could be conditionally knocked out in CD8+ T cells. Using their vaccine model, the researchers showed that TCF-1 was required for the memory responses generated by anti-CTLA-4, but not anti-PD-1. Then, using their OVA vaccine model, they showed that deletion of Tcf7 in CD8+ T cells reduced the frequency of antigen-specific T cells upon rechallenge in anti-CTLA-4-treated, but not anti-PD-1-treated groups, suggesting that TCF-1 contributes to optimal memory responses. Neither treatment was affected by the deletion of TOX.

Overall, this research helped to elucidate important distinctions between the modes of action of different checkpoint blockade antibodies. Anti-CTLA-4 mediated enhanced memory responses by preserving TCF-1+ T cells, and this effect was dependent on the contributions of CD4+ T cells, while anti-PD-1 promoted a TCF1-TOX+ phenotype that yielded less effective immune memory responses upon rechallenge.

Write-up and image by Lauren Hitchings

Meet the researcher

This week, first author Stephen Mok answered our questions.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

The most surprising finding was that anti-CTLA-4 generates a greater memory response than anti-PD-1. While immune checkpoint therapies are known to induce durable antitumor response, it remains unclear whether these arise from memory mechanisms associated with CTLA-4 or PD-1 blockade. Our study revealed distinct differences in memory T cells generated by the two treatments, examining their frequency, functionality, and transcription factors. Our results highlight how CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade differ in promoting memory, advancing our understanding of how immune checkpoint therapies sustain long-term immunity.

What is the outlook?

The outlook of our research is to deepen the understanding of how checkpoint inhibition impacts immunologic memory and its enduring effects on the immune system. Our findings suggest that anti-CTLA-4 generates a greater memory response than anti-PD-1 via TCF-1, providing molecular insights into the long-term immune response. It helps explain the durability of responses observed in patients, and offers a foundation for exploring the mechanisms of immunologic memory. Further investigation into checkpoint therapies and memory formation will advance our understanding of their long-term impacts, and guide the development of more effective cancer immunotherapies.

What was the coolest thing you’ve learned (about) recently outside of work?

Recently, I have taken up running as a hobby, often running at Hermann Park, next to MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. I ran my first marathon in San Francisco in July 2024, and am now preparing for my second marathon in Los Angeles in March 2025. Through marathon training, I have learned the importance of grit and persistence — a lesson that applies to science as well. We may encounter setbacks or failures, but we must remain persistent and keep pushing forward, just like in a race.