Few patients with advanced cancer respond or have durable response to current immunotherapies. One of the challenges is that neoantigen-specific T cell responses only rarely spontaneously arise in many tumors. Therefore, therapies that trigger the induction of neoantigen-specific T cells, such as vaccination, have the potential to increase the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). In a recent study published in Nature Medicine, Lopez et al. presented data on a phase 1 trial assessing the cancer vaccine therapy autogene cevumeran in various advanced cancer types.

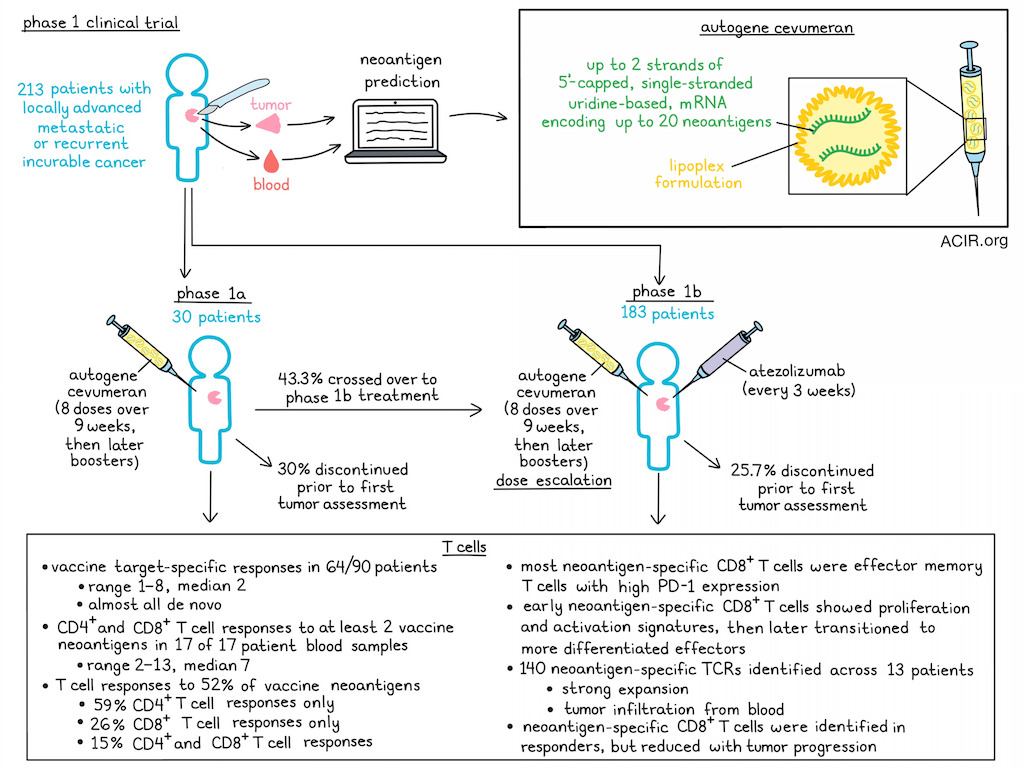

Autogene cevumeran is an individualized neoantigen vaccine consisting of up to two 5’-capped single-stranded uridine-based mRNA molecules encoding a total of up to 20 predicted neoantigen epitopes linked by short glycine- and serine-rich linkers, encapsulated in a lipoplex formulation.

In an ongoing trial, patients with locally advanced metastatic or recurrent incurable malignancies were included. In the phase 1a part of this study, patients received autogene cevumeran monotherapy, while in the phase 1b part, patients received the therapy in combination with atezolizumab in dose escalation cohorts. DNA and RNA were isolated from blood and tumor and evaluated with a computational pipeline to detect neoantigens for each patient. Across 33 study sites, 213 patients were enrolled, with 30 patients in phase 1a and 183 in phase 1b. Patients received 8 doses of autogene cevumeran intravenously (i.v.) during the first 9 weeks (induction), followed by booster doses until disease progression. Those receiving atezolizumab, received it i.v. on day 1 of the regimen, repeated every 3 weeks until disease progression.

Patients discontinued treatment due to disease progression at or before the first tumor assessment and before completion of the induction phase in 30% of cases in the phase 1a and 25.7% of cases in the phase 1b study. Of the phase 1a cohort, 43.3% crossed over to the combination treatment. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) were observed in 90% of those treated with monotherapy, of which 3 patients had a grade 3 adverse event (AE). One dose-limiting toxicity of grade 3 cytokine release syndrome was observed at the 100 μg dose, which resolved with supportive care. In the combination cohort, no new signals were observed, and AEs were consistent with atezolizumab monotherapy.

To characterize therapy-induced T cell responses, neoantigen-specific T cells were analyzed at baseline and after the induction phase. In 64/90 analyzed patients, ex vivo ELISPOT T cell responses against ≥1 (median 2; range 1-8) of the encoded neoantigens could be observed in both treatment cohorts. Almost all therapy-specific neoantigen T cell responses were induced de novo, with very few amplified pre-existing T cell responses.

Blood samples from 17 patients were analyzed for CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses following in vitro stimulation. All patients had CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cell responses against at least two neoantigens (median 7; range 2 - 13) included in the vaccine. Overall, T cell responses against 52% of neoantigens were detected, of which 59% were CD4+ T cell responses only, 26% were CD8+ only, and 15% were both. Neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells were first detectable approximately 3 weeks after start of treatment and continued to expand for the first months. In some patients, these cells reached single-digit percentages among circulating T cells. Most of the induced neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells were effector memory T cells with high levels of PD-1.

To study the differentiation pathway, Lopez et al. performed a longitudinal analysis of neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Among studied patients, T cells were reactive to 26 unique epitopes (1-5 per patient). These CD8+ T cells showed a proliferative and early activation signature at 22, 43, and 64 days after treatment start. At ≥100 days of treatment, the cells underwent a transition from early- to late-differentiated effector phenotypes.

The TCRs of the CD8+ T cells most enriched after 8 vaccination cycles were further assessed by a combination of bulk and single cell TCR sequencing. Across 13 analyzed patients, 140 neoantigen-specific TCRs were detected. These constituted a large portion of the post-vaccination circulating CD8+ T cell repertoires, suggesting strong expansion. To determine whether the cells detected in the periphery could infiltrate the tumor, on-treatment tumor samples from 10 patients were analyzed. Almost all neoantigen-specific TCRs detected in the blood were also found in the tumor biopsies in 8/10 patients. TCR clonotypes specific to ≤6 neoantigens were detected in the tumors, comprising up to 7.2% of all infiltrating CD8+ TCR clonotypes.

Due to small sample sizes for each tumor type and heterogeneous patient and immunogenicity data, clinical activity could not be correlated with immune responses. However, patients with higher numbers of metastases or previous therapies, and those with higher lactate dehydrogenase or C-reactive protein levels in blood at baseline were more likely to progress on treatment, while those with high tumor expression of activated immune cell infiltrate, immune checkpoints, antigen presentation-related genes, and other immune signaling genes markers had a reduced risk of progression.

Four patients with objective responses were analyzed in-depth. A patient had a complete response (CR) after 8 doses of monotherapy, which lasted 21 months. De novo T cell responses to 7 of 16 targeted neoantigens were detected. There were 12 CD8+ TCR clonotypes, which constituted up to 10% of the circulating CD8+ TCR repertoire at various timepoints. There were also CD4+ responses against 2 neoantigens. The CD8+ T cell responses persisted at high levels from the CR until disease progression, when only a small fraction of CD8+ and none of the CD4+ TCRs were detectable in the blood. In another patient with a CR for 8.2 months, which started after 9 doses of combination treatment, T cell responses against 3/20 neoantigens were detected. Another patient had a partial response (PR; 9.9 months), including a reduction of lung metastases. Strong T cell responses were detected, and 11% of CD8+ T cells in the blood had TCRs specific to two neoantigens. Once the patient experienced progressive disease, there was a decrease in neoantigen-specific TCRs in the periphery. Finally, a patient who first progressed on treatment, but later responded with a PR had T cell responses against 7 of 20 targeted neoantigens. At 5 months after treatment, a biopsy of a target lesion showed neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells that constituted 2.5% of all tumoral lymphocytes.

In total, this study showed that therapy was feasible, with manageable toxicities. The induction of neoantigen-specific T cell responses suggests potential beneficial therapy effects, and further specific cohort studies will be needed to establish efficacy. Additionally, testing of this therapy strategy in earlier lines of treatment might also improve outcomes. Phase 2 trials assessing these questions are currently ongoing.

Write-up by Maartje Wouters, image by Lauren Hitchings