Since the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into tumors predicts survival and response to immunotherapy in many patients, Jansen et al. examined the CD8+ T cell response against human cancer in order to understand why some tumors have high CD8+ T cell infiltration while others do not, and to uncover the mechanisms behind the antitumor T cell response. The results, recently published in Nature, indicate that high CD8+ T cell infiltration depends on the ability of stem-like CD8+ T cells – residing within antigen-presenting niches in the tumor – to generate terminally differentiated effector T cells.

The researchers began by collecting tumor tissue from 68 patients with kidney cancer and measuring intratumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration by flow cytometry. CD8+ T cell infiltration ranged from 0.02% to more than 20% of total tumor cells, and did not correlate with clinical parameters (patient age, disease stage, and other typically used patient grading systems). Patients who had CD8+ T cell infiltration below 2.2% tended to have much more rapid progression after surgery compared to patients with a higher percentage of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes (TILs).

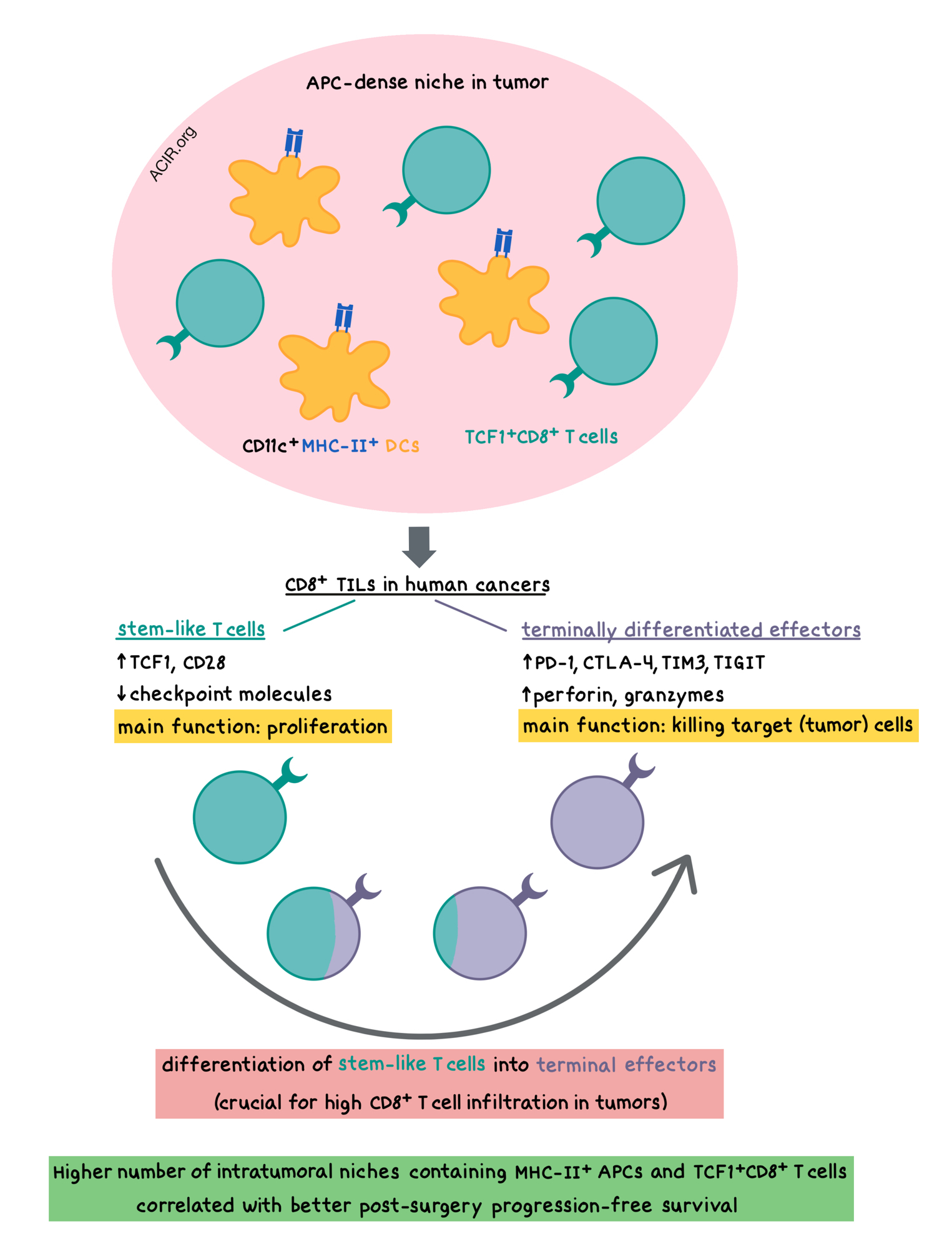

TIL composition analysis revealed one subset of cells that resembled exhausted CD8+ T cells, with high expression of checkpoint molecules, including PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM3, and TIGIT; and another subset of TILs with low levels of checkpoint molecules and high expression of the costimulatory CD28 molecule, as well as the transcription factor TCF1, which is associated with a stem-like T cell population in chronic viral infections. Upon in vitro stimulation, the stem-like TCF1+TIM3-CD28+ T cells isolated from tumors consistently proliferated, while the checkpoint-high PD-1+TIM3+ T cells did not. After proliferating, the stem-like cells upregulated PD-1, TIM3, and CD244, and downregulated TCF1, indicating their ability to differentiate into terminal effector-like T cells. Confirming this, TCR repertoire analysis showed significant clonal overlap between the two populations.

In poorly infiltrated kidney, bladder, and prostate tumors, the stem-like CD8+ T cells were present in very low numbers, but rarely were accompanied by the presence of terminally differentiated, exhausted-like cells. In contrast, highly infiltrated tumors had a significant presence of the terminally differentiated TIM3+ cells. These observations suggest that the magnitude of the intratumoral T cell response depends on the ability of the stem-like T cells to generate terminally differentiated T cells.

Exploring this hypothesis, the researchers utilized RNAseq and showed that the terminally differentiated T cells expressed elevated levels of checkpoint molecules as well as perforin and granzymes. The stem-like cells had increased levels of costimulatory molecules (e.g. CD28, CD226, CD2) and survival-related genes (e.g. IL7R, IL2RA [encoding CD25]). Whole-genome DNA methylation analysis revealed major epigenetic changes, primarily demethylation, and confirmed that the main function of the stem-like TILs was to proliferate, while the main function of the terminally differentiated TILs was to kill target cells. This compartmentalization of functions was regulated by distinct transcriptional and epigenetic programs.

Given the surprising localization of stem-like T cells within the tumors (studies in chronically-infected mice showed that such cells were present only in lymphoid tissue), Jansen et al. hypothesized that a lymphoid-like microenvironment might exist within the tumors that would support survival of these T cells. Analysis of the intratumoral antigen-presenting cells (APCs) across kidney, prostate, and bladder tumors revealed a highly significant correlation between the presence of CD11c+MHC-II+ dendritic cells and the number of stem-like CD8+ T cells. There was no correlation between macrophages and stem-like CD8+ T cells. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that the stem-like TCF1+CD8+ T cells tended to preferentially reside in APC-dense niches within the tumor, while TCF1-CD8+ T cells were distributed throughout the tumor. These niches were predominantly located inside the stromal barrier of the tumor, and they resembled the T cell zones of lymphoid tissues. Moreover, the presence of these niches was correlated to increased levels of lymphatic and blood vessels in the tumor. In contrast, the presence of tertiary lymphoid structures, which were observed primarily outside the tumor border, did not correlate with overall CD8+ T cell infiltration.

Finally, to understand tumor immune escape, the researchers imaged tumor tissue that was surgically removed from 26 patients with kidney cancer. They found that patients whose disease was controlled after surgery had a significantly higher number of niches containing MHC-II+ APCs and TCF1+CD8+ T cells compared to patients with poor progression-free survival (a >10-fold difference in niche numbers among the Stage III patients). The prognostic effect of APC niches was independent of tumoral expression of PD-L1, which did not correlate with TIL levels or patient survival.

Together, this high-resolution quantitative and spatial snapshot of multiple tumors with known clinical outcomes suggests that tumors may escape CD8+ T cell-mediated destruction either by preventing the formation of intratumoral APC niches or by destroying such niches. Furthermore, the impaired T cell response in some human cancers may be due not to the accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells or tumoral PD-L1 expression, but due to inefficient stimulation of stem-like CD8+ T cells within intratumoral APC niches, and the resulting failure to generate sufficient numbers of terminally differentiated CD8+ T cells in the tumor.

by Anna Scherer

Meet the researcher

This week, Haydn Kissick and Carey Jansen answered our questions

What prompted you to tackle this research question?

Tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes are a predictor of good clinical outcomes in nearly every cancer type, as well as a predictor of the response to immunotherapies, such as checkpoint blockade. However, we sought to tackle a more basic question at the root of these associations: why some patients’ tumors have many infiltrating T cells, while others do not? In seeking to answer this question, we hoped to uncover mechanisms that prompt or maintain immune infiltration into tumors, which could then be applied to developing new or to improving existing therapeutic strategies.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

Our finding of the TCF1+ stem-like CD8+ T cells in the tumor tissue, rather than only in the lymphoid tissue, was a surprising aspect of our study. In murine models of chronic infection where analogous TCF1+ stem CD8+ T cells were first defined, these cells were found only in lymphoid tissue. Our finding of stem-like CD8+ T cells in the tumor tissues led to our hypothesis that the establishment of a lymphoid-like environment in the tumor tissue may provide for the survival of the stem-like CD8+ T cells.

What was the coolest thing you’ve learned (about) recently outside of work?

HK: Having traveled to Hawaii for Christmas, I found out that it is the most isolated location in the world, and provides almost half of the world’s pineapples!

CJ: My alma mater, the University of Virginia, is located in central Virginia, known for its beautiful blue ridge mountains and home to many lovely vineyards and wineries. On a recent visit to an area winery, I sampled a new-to-me type of wine, a Gruner Veltliner. Originally native to Austria, a slow ripening season at steep elevations imparts an intense acidity to the wine, which may be so intense that some people can't taste it and may taste a hint of sweetness instead.