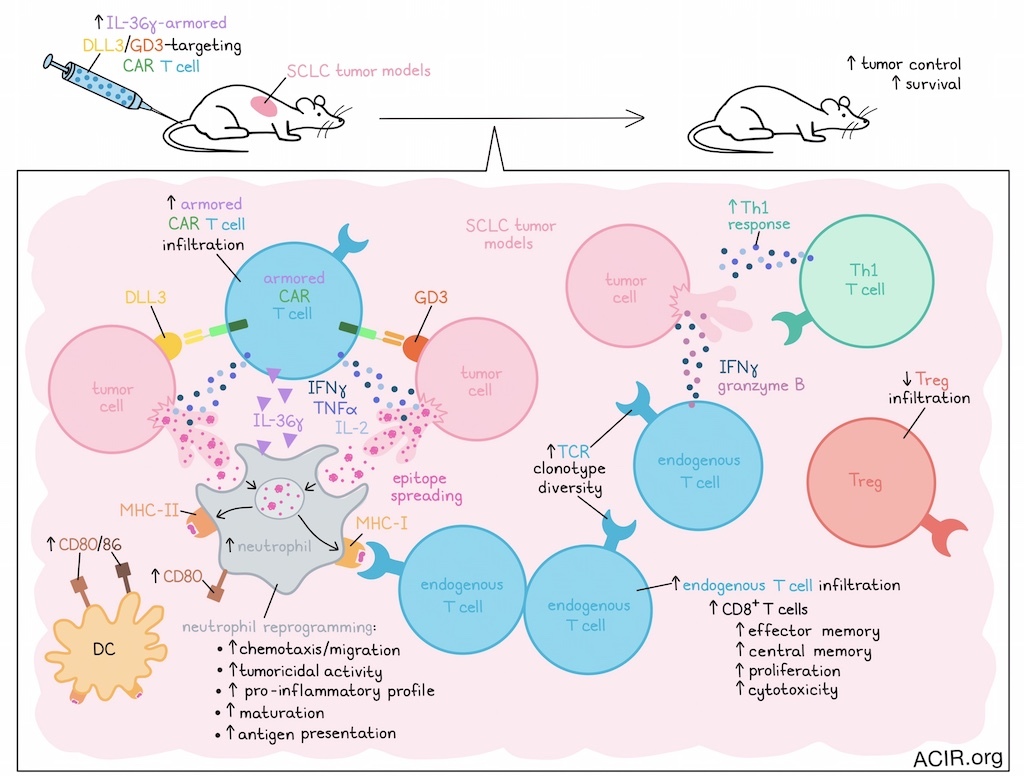

Several challenges limit CAR T cell efficacy in solid tumors, including the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), tumor heterogeneity, and downregulation of CAR target antigen expression on tumor cells. In a recent publication in Cancer Cell, Zuo et al. assessed the armoring of dual-targeting CAR-T with IL-36γ, which helped to overcome these challenges in unexpected ways.

The researchers started by confirming delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) and ganglioside (GD3) as therapeutic targets for small cell lung cancer (SCLC). TCGA data analysis of 110 SCLC cases revealed heterogeneous DLL3 expression, with a negative correlation between DLL3 and ST8SIA1 (the gene encoding a key enzyme involved in GD3 synthesis). Additionally, patient sample analysis showed that cells with low expression of one antigen typically expressed high levels of the other, suggesting targeting both might improve efficacy.

T cells co-expressing DLL3- and GD3-targeting CARs were cytotoxic in vitro against DLL3/GD3 double-positive human SCLC cell lines. The dual CAR-T were more cytotoxic and produced more IFNγ, IL-2, and TNFα than irrelevant or single-target CAR-T cells. Only the dual CAR-T cells could eradicate a mixture of DLL3-KO and GD3-KO SHP77 cells.

In a metastatic SCLC xenograft model, single-targeting CAR-T had limited antitumor effects, but dual CAR-T cells completely eradicated tumors. In a subcutaneous SCLC model, all mice were cured and had high tumoral CAR-T cell infiltration. There were no signs of off-target toxicity.

Based on their earlier research, Zuo et al. then assessed whether IL-36γ armoring of the dual-targeting CAR-T could increase the therapeutic efficacy in an immunocompetent mouse model. Given their previously established therapeutic efficacy in SCLC models, IL-18-armored CAR-T were used as controls. In mice bearing liver metastatic SCLC, unarmored CAR-T treatment had no antitumor effects, while both types of armored CAR-T induced tumor regression and improved survival. However, complete tumor eradication was only achieved with the IL-36γ armor.

Assessment of liver metastases in this model showed limited infiltration of unarmored CAR-T, while there was significant infiltration of CAR-T armored with IL-36γ or IL-18. Additionally, both armored CAR-T products increased the number of endogenous IFNγ- and granzyme B-expressing CD8+ T cells. However, only the IL-36γ armored CAR-T induced Th1 responses and DC expression of CD80/CD86, along with decreased Treg infiltration.

The researchers then moved on to the poorly immunogenic, aggressive B16F10-OVA melanoma model, which was edited to overexpress GD3. Without lymphodepletion, treatment with IL-36γ-armored CAR-T improved survival, whereas unarmored or IL-18-armored CAR-T were not effective. Only the IL-36γ-armored CAR-T impacted endogenous immune cells in the TME, with a decrease in Tregs. In mice treated with the IL-36γ-armored CAR-T, tumors exhibited increased numbers of CD8+ T cells with effector memory and central memory phenotypes, and a large percentage of these CD8+ T cells expressed proliferation and cytotoxicity markers.

To determine whether endogenous T cell responses added to the CAR-T antitumor effects, Zuo et al. assessed the antitumor activity of post-treatment spleen CD8+ T cells. These CD8+ T cells exhibited a strong IFNγ response against tumor cells, independent of CAR antigen expression, suggesting epitope spreading. To test this, mice were rechallenged with SCLC and melanoma tumor variants not expressing the CAR antigens. Only mice previously treated with the IL-36γ armored CAR-T rejected these tumor cells. When mice were lymphodepleted before treatment with the armored CAR-T, tumors were eradicated, but rechallenge with antigen-negative tumor cells resulted in tumor growth. These data suggest that endogenous T cell responses improved the efficacy of the armored CAR-T.

Epitope spreading in response to IL-36γ armored CAR-T was confirmed in the B16F10-OVA model, in which mice receiving IL-36γ armored CAR-T showed expanded gp100-specific CD8+ T cells and OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Additionally, TCR clonotype diversity among CD8+ T cells increased after armored CAR-T treatment. Analysis of clonotypes that were present after IL-36γ-armored CAR-T treatment, but absent in untreated controls suggested that the T cell epitope diversity increased due to de novo induction of unique TCRs.

Since IL-18-armored CAR-T eliminated tumors, but did not induce endogenous tumor-specific T cell responses, the researchers hypothesized that immunomodulation of the TME may be responsible for the epitope spreading observed with IL-36γ-armored CAR-T. To assess this, tumor-infiltrating immune cells from SCLC-bearing mice 4 days after CAR-T treatment were subjected to scRNAseq. Neutrophils were the only immune population consistently enriched in the IL-36γ-armored CAR-T-treated group. Additionally, there was increased expression of genes associated with neutrophil chemotaxis and migration. The neutrophils in these tumors had a pro-inflammatory and tumoricidal transcriptional profile.

To determine whether neutrophils were essential for the observed tumor rejection and epitope spreading effects, mice depleted of neutrophils were treated with the armored CAR-T. In these mice, treatment did not result in tumor control or induction of tumor-specific T cell responses.

Clustering of the neutrophil scRNAseq data revealed 9 major clusters, of which 4 clusters were highly enriched, and 3 clusters were unique to the IL-36γ armored CAR-T treatment group. The highly enriched clusters were characterized by genes associated with antigen presentation, suggesting these neutrophils had features of professional APCs. The clusters unique to IL-36γ armored CAR-T were characterized by maturation and tumoricidal activity genes. In contrast, clusters enriched in the other treatment groups were characterized by late-stage neutrophils that expressed pro-tumor genes. The presence of MHC-II+CD80+ neutrophils in the TME was confirmed by flow cytometry. These APC-like neutrophils could be induced in vitro by coculturing murine bone marrow neutrophils with supernatant from activated IL-36γ-armored CAR-T, and these reprogrammed neutrophils were tumoricidal.

To confirm the APC functionality of these neutrophils, naive T cells from pmel-1, OT-I, and OT-II mice were cocultured with CAR-T cell supernatant-pre-treated, B16F10-OVA-exposed neutrophils. Neutrophils pre-treated with IL-36γ armored CAR-T supernatant killed tumor cells, processed and presented gp100 and OVA peptides on both MHC-I and MHC-II molecules, and activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Similar results were obtained with human neutrophils.

In conclusion, these data show that armoring CAR-T with IL-36γ improved CAR-T efficacy against solid tumors, without the need for prior lymphodepletion. Through reprogramming of neutrophils in the TME, endogenous antitumor T cell responses were induced, overcoming challenges regarding heterogeneous tumor antigen expression.

Write-up by Maartje Wouters, image by Lauren Hitchings

Meet the researcher

This week, first author Yihan Zuo answered our questions.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

The most surprising finding is that IL-36γ armored CAR T cells cured solid tumors in a neutrophil-dependent manner, unlike conventional CAR T cell therapies, which mostly rely on CAR T cell-mediated tumor killing. What is even more striking is neutrophils reprogrammed by IL-36γ armored CAR T cells exhibited antigen-presenting function and could induce de novo priming of naive CD8+ T cells, a unique feature which is believed to be restricted to professional antigen-presenting cells like dendritic cells.

What is the outlook?

The most straightforward outlook is to move our findings into clinics. Building on work from Dr. Renier Brentjens’s group, a paradigm-shifting aspect of IL-36γ armored CAR T cell therapy is that it does not require prior lymphodepletion to exert its therapeutic efficacy, since it does not rely on persistence of CAR T cells, but instead active endogenous immune effectors to mediate long-term antitumor responses. Follow-up studies will also aim to explore the underlying mechanisms in neutrophil reprogramming, including the neutrophil progenitors, key driving cytokines, and associated signaling pathways, and test whether antitumor neutrophils can be induced ex vivo and developed into a new form of adoptive cell therapy for cancer.

What was the coolest thing you’ve learned recently outside of work?

Recently, I’ve become obsessed with baking all kinds of cakes – especially chiffon cakes and Basque cheesecakes. It has been surprisingly enjoyable to experiment with different textures and techniques. In some ways, it feels a bit like running experiments in the lab: precise measurements, careful timing, and a touch of creativity. But the best part is that the “results” are delicious and can be shared with friends and family.