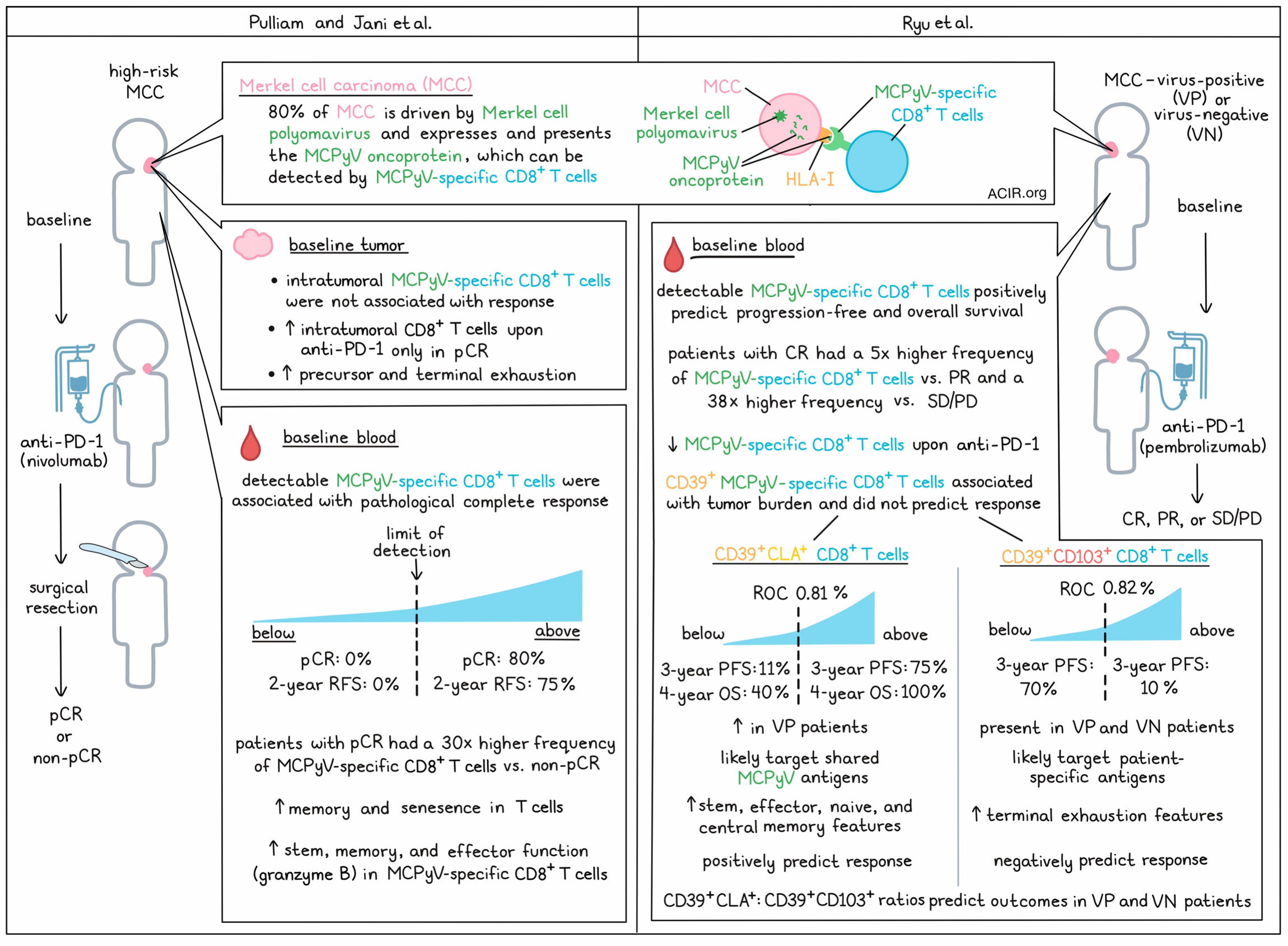

Tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are known to be important in antitumor immunity, but identifying them in patient samples is often a challenge. In order to study tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell as potential biomarkers of response, two groups, Pulliam and Jani et al. and Ryu et al., recently evaluated them in Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) – about 80% of which are driven driven by Merkel cell polyomavirus and consistently express MCPyV oncoproteins that are not found in healthy tissues. In MCC, which is relatively responsive to first-line PD-1/PD-L1-targeted therapies, both groups identified tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as biomarkers of response to treatment that could be identified in baseline blood samples. Both papers were published in Cell Reports Medicine.

Pulliam and Jani et al. began by establishing a panel of HLA-I multimers containing peptides from MCPyV that could be used to identify cancer-specific T cells from patients with virus-positive (VP)-MCC. This panel was then used to evaluate PBMCs from pre- and on-treatment blood samples from patients with high-risk MCC who received neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy (nivolumab) for roughly 4 weeks prior to a complete surgical resection of their disease. This showed that the presence of MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood at baseline was highly associated with a pathological complete response (pCR). In patients with MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells above the limit of reliable detection, 80% had a pCR, and the recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate at two years was 75%. By contrast, in patients with MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells below the limit of reliable detection, 0% had a pCR, and the RFS rate at 2 years was 0%. Further, the relative frequencies of MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells were also positively associated with response. In patients with a pCR, the median pre-treatment frequency of MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells was 30-fold higher than in patients with a non-pCR.

Next, Pulliam and Jani et al. performed a similar assessment of MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells in tumors. However, unlike in peripheral blood, intratumoral MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells did not correlate with response, though treatment significantly increased overall intratumoral CD8+ T cells in patients with a pCR.

Like Pulliam and Jani et al., Ryu et al. also examined a cohort of patients with MCC who were treated with an anti-PD-1 antibody (pembrolizumab). In this study, blood samples were taken prior to and over the course of treatment from patients with diverse clinical responses (complete response [CR], partial response [PR], or stable or progressive disease [SD/PD]) and viral states (virus-positive [VP] or virus negative [VN]). These researchers too found that baseline frequencies of blood MCPyV-specific cells correlated with response, as the mean frequency of MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells in CR patients was 5 times higher than in PR patients and 38 times higher than in SD/PD patients. Patients with detectable MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells in their blood at baseline also had improved overall and progression-free survival compared to patients that did not. Anti-PD-1 treatment was associated with a decrease in MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with CR, but not in patients with PR or SD/PD.

Investigating the phenotypic differences between MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood versus the tumor, Pulliam and Jani et al. used matched tumor and blood samples from 8 patients with advanced MCC before and after treatment with nivolumab – 5 of which could be properly analyzed. Employing various analyses, they found that while most intratumoral T cells fell into precursor and terminally exhausted clusters, circulating T cells were less exhausted and showed signs of memory and senescence. Looking specifically at MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells, those in tumors were more likely to be exhausted, while those in the blood were more likely to show stem, memory, and effector characteristics, including expression of granzyme B.

Similarly, Ryu et al. performed deep immune phenotyping of blood samples and found that MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells expressed various co-stimulatory and inhibitory receptors, along with markers of proliferation, activation, and effector function. Notably, these T cells were highly enriched for CD39 (associated with tumor-specific exhausted CD8+ TILs) as well as CLA (a skin homing marker) and CD103 (a tissue circulating marker). Further, the levels of these markers were maintained over the course of therapy.

Evaluating clusters of CD8+ T cells, Ryu et al. found that baseline CD39 alone was mostly reflective of tumor burden and did not predict outcomes. However, a cluster of CD39+CLA+ CD8+ T cells that was higher in VP patients did positively predict patient outcomes. After using ROC to determine a threshold of 0.81%, the researchers found that patients with a baseline frequency of CD39+CLA+ CD8+ T cells above the threshold had a progression-free survival (PFS) rate of 75% at 3 years and an overall survival (OS) rate of 100% at 4 years, while those with a frequency below the threshold had a PFS rate of 11% at 3 years and an OS rate of 40% at 4 years.

Ryu et al. also identified a cluster of CD39+CD103+ CD8+ T cells, present in both VP and VN MCC, that correlated with baseline tumor burden and negatively predicted patient outcomes. With a ROC threshold of 0.82%, the researchers found that patients with frequencies of CD39+CD103+ CD8+ T cells above the threshold had a PFS rate of 10% at 3 years, while those with frequencies below the threshold had a PFS of 70% at 3 years. Similar patterns were observed with overall survival, even when VN patients were included in the analysis.

Given the opposite nature of these two subsets, Ryu et al. showed that the CD39+CLA+/CD39+CD103+ ratio could predict improved PFS and overall survival in both VP and VN patients. Compared to one another, CD39+CLA+ populations were more clonal, more likely to be tumor-specific, and had a higher publicity (a measure of clone sharing) compared to CD39+CD103+ populations, consistent with CD39+CLA+ T cells targeting more shared MCPyV antigens and CD39+CD103+ cells targeting more private or patient-specific antigens. Further, in phenotypic evaluations, CD39+CLA+ cells showed features of stemness, effector function, and naive/central memory, while, CD39+CD103+ showed features of terminal exhaustion. These results suggest that while both populations exhibit some degree of activation and exhaustion, CD39+CLA+ cells remained more functional, while CD39+CD103+ cells were more terminally exhausted.

Overall, the results of these two studies show that in patients with MCC, baseline MCPyV-specific CD8+ T cells can help to predict which patients will and will not respond to anti-PD-1. Pulliam and Jani et al. further noted that MCPyV-specific T cells were more functional and predictive of response than their intratumoral counterparts, while Ryu et al. identified two distinct subsets of MCPyV-specific T cells in blood that could positively and negatively predict outcomes. The identification of these biomarkers may prove useful in the clinic, as they could help to predict responses, stratify patients with MCC for optimal treatment, and/or suggest new therapeutic opportunities.

Write-up and image by Lauren Hitchings

Meet the researcher

This week, Paul Nghiem, lead author on “Circulating cancer-specific CD8 T cell frequency is associated with response to PD-1 blockade in Merkel cell carcinoma” answered our questions.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

We and others have been searching for nearly a decade for what predicts response or non-response to immunotherapy. I really thought that the number of intratumoral CD8+ T cells, or the expression levels of class I HLA or PD-L1 on the cancer cells would be an important determinant. None of those things turned out to matter. We were surprised to find that a very important determinant was the number of cancer-specific T cells in the blood. In retrospect, this makes sense. It is rather like troops being brought into a distant battlefield. Data from two independent clinical trials indicate the exact same thing, so we feel quite confident this is “real”.

What is the outlook?

It has not been feasible to look at cancer-specific T cells for most cancers, because the cancer antigens recognized by the immune system are different between each person. For the cancer we have focused on, Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) caused by the Merkel cell polyomavirus, all patients share the same cancer-specific immune targets. This greatly facilitates identification of cancer-specific T cells. Even in this simple case, the specialized tools we used were expensive, complex to use, and could not be used in a routine clinical setting. Our current goal is to use the information we have gleaned thus far to find more simple ways to identify cancer-specific targets in MCC and other cancers. This should help us understand who will respond, and how to help those who do not respond to currently available immune therapies.

What was the coolest thing you’ve learned (about) recently outside of work?

I am half Vietnamese, and was born in the US. This December, I traveled with my family to see Vietnam and meet distant relatives. It was amazing and encouraging to see how Vietnam is now thriving after centuries of being attacked and occupied by numerous countries.