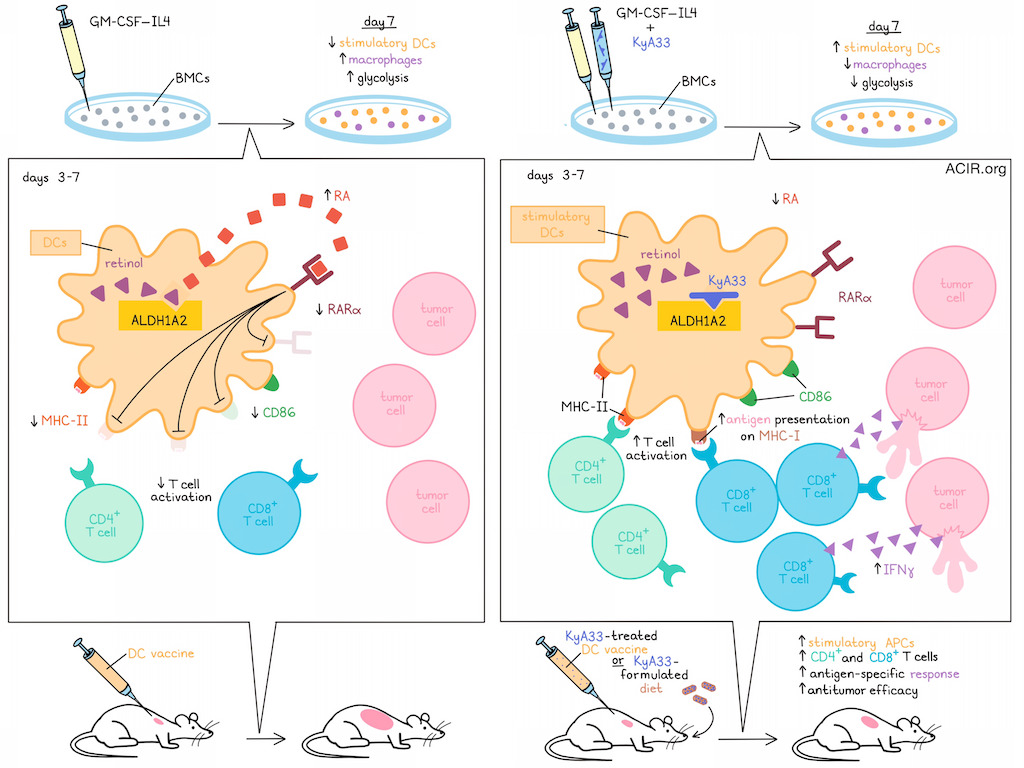

As professional antigen-presenting cells, dendritic cells have been utilized as whole-cell vaccines, but their clinical efficacy has thus far been limited. Fang et al. found that a common protocol of using GM-CSF and IL-4 to induce bone marrow cells (BMCs) into DCs for use in vaccines led to a decline in antigen presentation and functional attenuation of DCs starting at day 3. Investigating this, the group identified autocrine retinoic acid (RA) as an inhibitor of DC function, and developed a drug to disrupt this tolerogenic feedback mechanism.

To begin, Fang et al. treated murine bone marrow cells with GM-CSF and IL-4 to generate DCs. Monitoring of CD11c, MHC-II, and CD86 showed that MHCIIhiCD86hi stimulatory APCs peaked at day 3, then declined through day 7, coinciding with a loss of peptide presentation. In search of a potential negative feedback mechanism, the researchers investigated retinoic acid (RA) – known to induce tolerance in other cells and settings. They found that culturing DCs in charcoal-stripped (CS) fetal bovine serum (FBS) to remove a metabolic precursor of RA yielded DCs that expressed higher levels of MHC-II and CD86, but were less viable than those cultured in normal FBS. This effect could be reversed by adding exogenous all-trans RA (atRA), suggesting that RA supports the expansion of attenuated APCs. Similar effects were also observed in other models, including in human cells.

The rate-limiting step in the generation of RA from retinol is controlled by retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs). Here, Fang et al. found that Aldh1a2 was the only ALDH1A isoform expressed in APCs at the RNA level, and that ALDH1A2 protein levels were detectable starting at day 3, and progressively increased through day 7 of APC differentiation. Expression of Aldh1a2 was also higher in CD11c+MHCIIdimCD86dim than CD11c+MHCIIbrCD86br cells. Further, expression of RARα, one of 3 RA receptors, decreased from days 3-7, suggestive of an autocrine RA-induced negative feedback loop.

To better understand the role of ALDH1A2, the researchers utilized two Aldh1a2-deletion mouse strains – a model for full-body Aldh1a2-knockout, and model for conditional knockout of Aldh1a2 specifically in CD11c+ APCs. GM-CSF–IL-4-induced APCs generated from both mouse strains showed loss of ALDH1A2 protein, an increase in stimulatory MHCIIhiCD86hi APCs, and increased amplitude of MHC-II and CD86 expression when cultured in normal FBS. The difference between Aldh1a2-knockout and wild-type lines was attenuated when both were cultured in CS-FBS (both showed increased MHC-II/CD86) or when both were treated with atRA (both showed reduced MHC-II/CD86).

Next, Fang et al. performed multiomic characterization of GM-CSF–IL-4-induced APCs from Aldh1a2-KO and WT mice, and found that both RNA and protein level expression of genes involved in DC maturation, antigen presentation, and T cell stimulation were increased in the KO cells. Gene set enrichment analysis also confirmed reduced vitamin A metabolism and increased DC maturation, and revealed reduced glycolysis in the KO cells, which was confirmed through metabolic profiling. Further investigation into this reduction in glycolysis showed that while the availability of glucose could impact DC maturation, the role of Aldh1a2KO was more significant, and ALDH1A2-induced changes in maturation were not predominantly due to the effect on glycolysis.

To investigate whether the loss of ALDH1A2 in APCs influences T cell activation, the researchers utilized a coculture model consisting of APCs, T cells, and OVA-expressing tumor cells. Here, T cell proliferation and IFNγ were increased when ALDH1A2 was knocked out from APCs. This was attributed to both increased antigen presentation on MHC-I and increased antigen-independent costimulation of T cells, but not on any paracrine signaling to T cells.

To take advantage of ALDH1A2 inhibition for therapeutic enhancements, the researchers performed high-throughput screening and identified ESPO1 as a potent and selective inhibitor of ALDH1A2; however, ESPO1 could not be made membrane permeable without losing its binding. Shifting gears, the researchers adapted their recently developed ALDH1A3 inhibitor, MBE130, and found a way to enhance its inhibitory activity toward ALDH1A2 while maintaining membrane permeability. Analysis of molecular interactions of this novel drug, termed KyA33, aligned with a rationale for its action as a dual inhibitor of both ALDH1A2 and ALDH1A3.

When KyA33 was added to GM-CSF–IL-4-induced BMC cultures, the resulting populations showed increased stimulatory DCs with increased functionality and reduced glycolysis, mirroring results from Aldh1a2KO models. This was confirmed to be due to KyA33-mediated inhibition of ALDH1A2 enzyme activity and the resulting reduction in RA production. Also, like in the Aldh1a2KO models, treatment with KyA33 enhanced APC-mediated T cell activation, both in ex vivo-induced and primary DCs.

Beyond inducing DCs, GM-CSF–IL-4 also induces macrophages. The researchers performed lineage tracking and found that while proportions of DCs (most of which were MHCIIhiCD86hi stimulatory DCs) decreased from days 3-7, proportions of CD115+ macrophages (which were mostly MHCIIloCD86lo) increased within the same timeframe. Administration of KyA33 significantly inhibited macrophage development, without impacting their expression of CD80, CD86, or MHC-II. KyA33 also enriched for DCs by day 7, but not day 3, suggesting that ALDH1A2 may suppress stimulatory APCs both by biasing differentiation toward macrophages and by dampening DC functionality. Additionally, KyA33 treatment did not affect glycolysis in either macrophages or DCs, suggesting that the reduced glycolysis observed in APCs was likely due to enrichment of less glycolytic DCs, rather than direct suppression of glycolysis.

Evaluating whether KyA33 could be used to improve DC vaccine efficacy, the researchers established a DC vaccine model using mouse APCs loaded with immunogenic peptides. KyA33 treatment of vaccine DCs enriched the percentages of stimulatory APCs and increased levels of antigen loading, resulting in stronger antitumor immunity. Further evidence supported that this was mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which were increased and showed stronger antigen-specific responses.

Considering the potential for therapeutic translation, the researchers found that KyA33 showed favorable pharmacological characteristics for use as an oral immunotherapeutic. DCs from mice fed with a KyA33-formulated diet were capable of enhanced T cell activation, particularly in the presence of a strong antigen. When mice bearing B16F10–GM-CSF tumors were fed a KyA33-formulated diet, they demonstrated increased proportions of stimulatory MHCIIhiCD86hi APCs, and reduced tumor growth, suggesting that KyA33 may also have potential as a single-agent cancer treatment.

Overall, these results show that using GM-CSF–IL4 to induce DCs also induces DC production of ALDH1A2, which enhances RA production and supports an autocrine feedback loop that promotes reduced DC functionality and enhanced macrophage differentiation. Use of KyA33 could interfere with these mechanisms to enhance DC functionality, T cell activation, and antitumor immunity, either in combination with DC vaccines or as a single-agent treatment.

Write-up and image by Lauren Hitchings

Meet the researcher

This week, first author Cao Fang and lead author Yibin Kang answered our questions.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

YK: We were quite surprised by how a metabolite could significantly influence the dynamics of APC development and DC functions. As the method to expand APCs in culture is well established, it has been taken for granted that when APCs are fully developed, they also acquire maximal activity. Cao carefully monitored this whole process and found that the development of APCs and their activity was not linearly correlated. Although 7 days of culture led to expansion of APCs, their activity peaked at day 3 and declined afterwards. By identifying retinoic acid, the metabolite of vitamin A, as the bottleneck factor responsible for this phenomenon, we now understand this process better, and with the ALDH1A2/3 inhibitors we developed, it is now possible to break this bottleneck to maximize the full potential of DC vaccines.

What is the outlook?

CF: Even though this mechanism was first discovered in cell culture, we have confirmed the enhancement of APC activity by treating mice directly with this inhibitor, suggesting broad applicability. The most immediate future direction is to investigate how this mechanism is involved in other immune-related conditions, including infections, autoimmune diseases, and different types of cancer. The ALDH1A2/3 inhibitors identified in this study may be further developed to improve the efficacy of different treatment modalities of cancer immunotherapy. In addition, this drug will be very useful for researchers who are studying the functional dynamics of retinoic acid signaling in other biological contexts, by facilitating an acute intervention of RA signaling through the pharmacological approach.

If you could go back in time and give your early-career self one piece of advice for navigating a scientific career, what would it be?

CF: Although I am still at an early stage of my scientific career, I would tell my younger self that while scientific discovery often appears smooth and linear in the literature, it is anything but that in reality. Research rarely follows a clear map or a predetermined path. Instead, it is more like a mining game, where you uncover scattered fragments that only gradually begin to make sense as you piece them together. Because of this, unexpected results should not cause panic. With patience and persistence, those fragments eventually connect, revealing the bigger picture. That moment is when science truly happens.