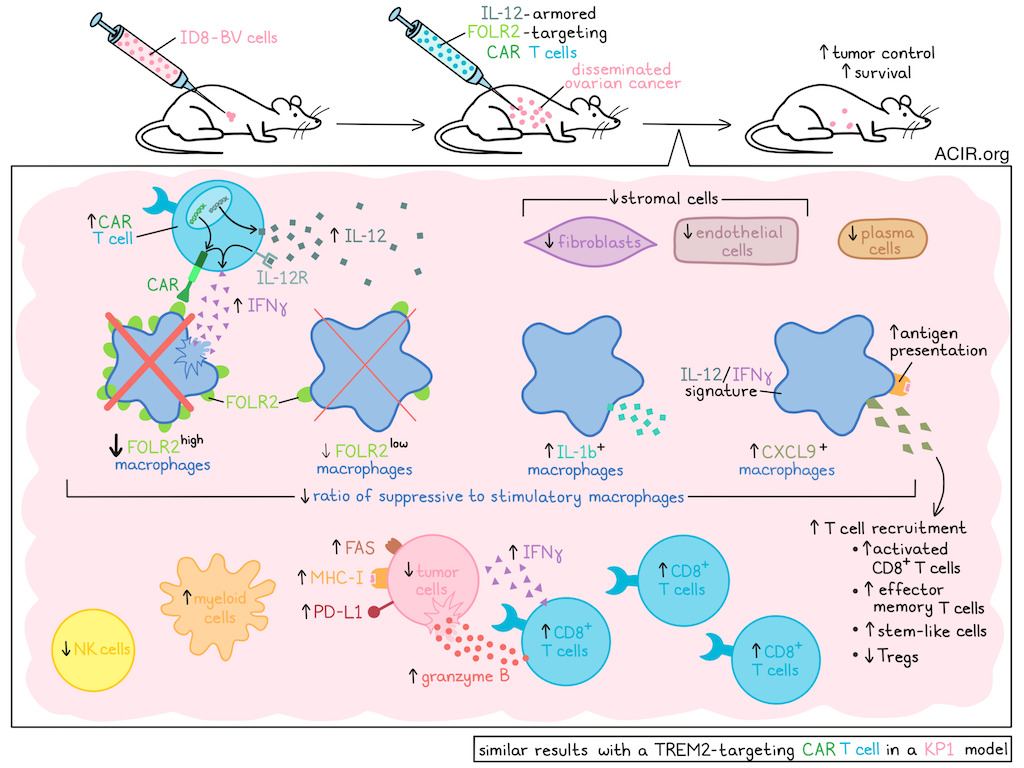

CAR T cell efficacy is limited in solid tumors due to their highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), which is partially and often significantly driven by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). Various therapies are in development to remodel the TME to improve immunotherapy efficacy. Mateus-Tique et al. developed an armored CAR-T strategy that aims to deplete TAMs and remodel the TME. Their results were recently published in Cancer Cell.

The researchers began by developing FOLR2-targeting CAR-T cells and assessing whether these cells could specifically deplete suppressive FOLR2+ TAMs in the TME in a model of advanced-stage ovarian cancer. In this model, mice develop disseminated tumors in the peritoneal cavity after intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ID8-BV cells. An anti-FOLR2 CAR vector was used to transduce CD8+ T cells, and the resulting CAR-T cells were reactive against FOLR2+ cells in vitro, including FOLR2+ macrophages collected from the ascites of ID8 tumor-bearing mice. In vivo, i.p.-injected CAR-T expanded, accumulated in the tumors, and depleted all FOLR2+ macrophages in the tumor and peritoneal lavage, but spared FORL2- macrophages. To test efficacy, immunocompetent mice were i.p. injected with ID8-BV, and after 8 days, mice were lymphodepleted and injected i.p. with the CAR-T. This resulted in a modest effect on survival. Further, CAR-T had limited antitumor effects in an orthotopic pancreatic tumor model, but induced a ~75% reduction in FOLR2+ TAMs.

The researchers then aimed to arm the CAR-T to deliver cytokines to further modulate the TME. A panel of armored CAR vectors encoding IFNα, IFNγ, IL-12, or sushi-IL-15 was assessed in combination with the anti-FOLR2 CAR. In vitro, each of the engineered CAR-T released its payload and killed FOLR2+ macrophages. To test in vivo effects, ID8-BV-bearing mice were lymphodepleted and i.p. injected with 1.5 x 106 CAR-T cells. The CAR-T with IFNα and IFNγ payloads did not improve efficacy, whereas the CAR-T with IL-12 and sushi-IL-15 payloads led to faster death, suggesting severe toxicity.

To reduce the toxicity of the IL-12-producing CAR-T, the researchers tested removing lymphodepletion and lowering IL-12 output from the vector using a destabilization domain (DD). The ID8-BV model was treated on day 8 with 1x106 IL-12.aFOLR2.CAR-T, DD.IL-12.aFOLR2.CAR-T, or control T cells, without prior lymphodepletion. The DD version induced complete remissions and did not impact weight, suggesting limited toxicity. The regular IL-12 version, at this dose and without lymphodepletion, also provided a survival benefit, with lower, but still present toxicity. A dose of 0.1x106 IL-12.aFOLR2.CAR-T cells, again without lymphodepletion, was tolerated and induced a 5–9-fold reduction in tumor burden and improved survival. At this dose, there were no signs of liver toxicity, and FOLR2-expressing Kupffer cells were not impacted, potentially due to lower FOLR2 expression. In an aggressive pancreatic cancer model, this dose of IL-12.aFOLR2-CAR-T cells, injected intravenously or i.p., also improved survival.

To investigate how macrophage-targeting CAR-T inhibited tumor growth without directly targeting tumor cells, the researchers examined the TME in the ID8-BV model. Ten days after treatment, the tumor-bearing omentum was subjected to spatial transcriptomics. This confirmed the elimination of cancer cells and a significant alteration of the TME. T cells and myeloid cells increased, while stromal cells, including fibroblasts and endothelial cells, and plasma cells decreased.

Clustering of the macrophages revealed that Folr2high macrophages were almost completely depleted, while Folr2low macrophages were partially depleted, suggesting an expression threshold to induce CAR-T killing. On the other hand, Cxcl9+ macrophages increased and accounted for more than 70% of macrophages in treated tumors. These macrophages expressed an IL-12/IFNγ signature, including genes involved in T cell recruitment and antigen presentation. Additionally, a closely related cluster was detected, consisting of IL-1b-expressing macrophages. The ratio of immune stimulatory-to-suppressive macrophages went from 0.5 in controls to 44 in the IL-12.aFOLR2-CAR-T-treated tumors.

Significant changes in the lymphoid compartment of the TME were also observed, including a 7-fold increase in activated CD8+ T cells and a 76% decrease in Tregs. Activated CD8+ T cells expressed increased levels of Ifng and Gzmb. Additionally, a 17-fold increase in effector memory T cells was observed (representing 8% of activated effector CD8+ T cells), as was a 50% increase in stem-like memory CD8+ T cells. NK cell frequency was reduced and likely did not contribute to antitumor effects, which was confirmed by NK cell depletion experiments.

Spatial analysis showed that, in CAR-T-treated tumors, cancer cells were more commonly located near Gzmb+Cd8+ T cells. After 11 days of treatment, there was a >3-fold increase in ID8-reactive CD44+IFNγ+CD8+ T cells in the spleen.

The analyses also revealed that FAS, MHC-I, and PD-L1 were upregulated on cancer cells in the IL-12.aFOLR2-CAR-T-treated group. To determine whether FAS upregulation contributed to the therapeutic benefit, FAS was knocked down in ID8 tumor cells. In this model, the therapeutic effect of the IL-12.aFOLR2-CAR-T was reduced, suggesting partially FAS-dependent activity.

Another marker of TAMs with immunosuppressive activity in various cancers is TREM2. The researchers assessed whether a CAR-T strategy targeting TREM2 with an IL-12 payload could induce similar antitumor effects. This strategy was tested in the KP1 lung cancer model, which contains TREM2+ macrophages. While a high dose (1.5x106) of the anti-TREM2-CAR-T with prior lymphodepletion resulted in only modest effects on survival in this model, treatment with low-dose IL12.aTREM2.CAR-T (without lymphodepletion) significantly reduced tumor burdens and prolonged survival. In the TME of these mice, similar changes were observed to those observed in response to IL-12.aFOLR2-CAR-T in ovarian tumors. Activated endogenous CD69+CD8+ T cells and macrophages with higher MHC-II and CD80 expression were detected after treatment. In this model, cancer cells also upregulated FAS in response to therapy.

These preclinical data suggest that targeting immunosuppressive TAMs and locally delivering IL-12 in aggressive tumors can remodel the TME and induce antitumor immunity. The lower dose and the lack of required lymphodepletion might improve treatment tolerability, potentially allowing combination treatments with other strategies, such as ICB.

Write-up by Maartje Wouters, image by Lauren Hitchings

Meet the researcher

This week, first author Jaime Mateus-Tique answered our questions.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

In bioengineering, few moments are more rewarding than seeing a strategy work exactly as designed. In this study, we report a paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy: IL-12–armored CAR T cells that target tumor-associated macrophages rather than tumor cells themselves. By recognizing stable macrophage markers, these engineered cells both eliminate immunosuppressive macrophages and concentrate IL-12 directly within the tumor microenvironment in a metastatic ovarian cancer model. This dual action, by resetting and reprogramming the tumor microenvironment, produced durable tumor control that exceeded expectations. It was achieved without lymphodepletion and with remarkably low cell doses, highlighting a promising new direction for treating solid tumors.

What is the outlook?

Our ultimate goal is to improve patients' lives, especially for those who have exhausted current treatment options. We are committed to advancing this therapy toward the clinic, recognizing that this will require careful, rigorous development. Key next steps include humanizing the CAR T cell targeting domains, and further restricting IL-12 release to the tumor microenvironment to optimize safety and efficacy. In parallel, our study generated extensive data on tumor immune reprogramming, offering new opportunities to enhance anti-cancer responses. By building on these insights, we aim to unlock additional therapeutic benefits and move closer to delivering transformative immunotherapies to patients in need.

Who or what has been a major source of inspiration or motivation for you throughout your career?

I was incredibly fortunate to meet and befriend Dr. Merad, who inspired me to pursue a career in biomedical science and join the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, ultimately leading me to its Institute of Immunology. Dr. Merad has led the field of immunology with remarkable vision and impact, fostering an environment that promotes innovation and collaboration. At the Institute, I found an extraordinary community of scientists with whom it has been a true pleasure to work. In particular, Dr. Brian Brown’s mentorship and ongoing support have been essential to my scientific development and exploration of new therapeutic strategies. Equally important, his entire laboratory fosters an atmosphere of collaboration, generosity, and mutual support, making it an exceptional environment for scientific discovery and personal growth.