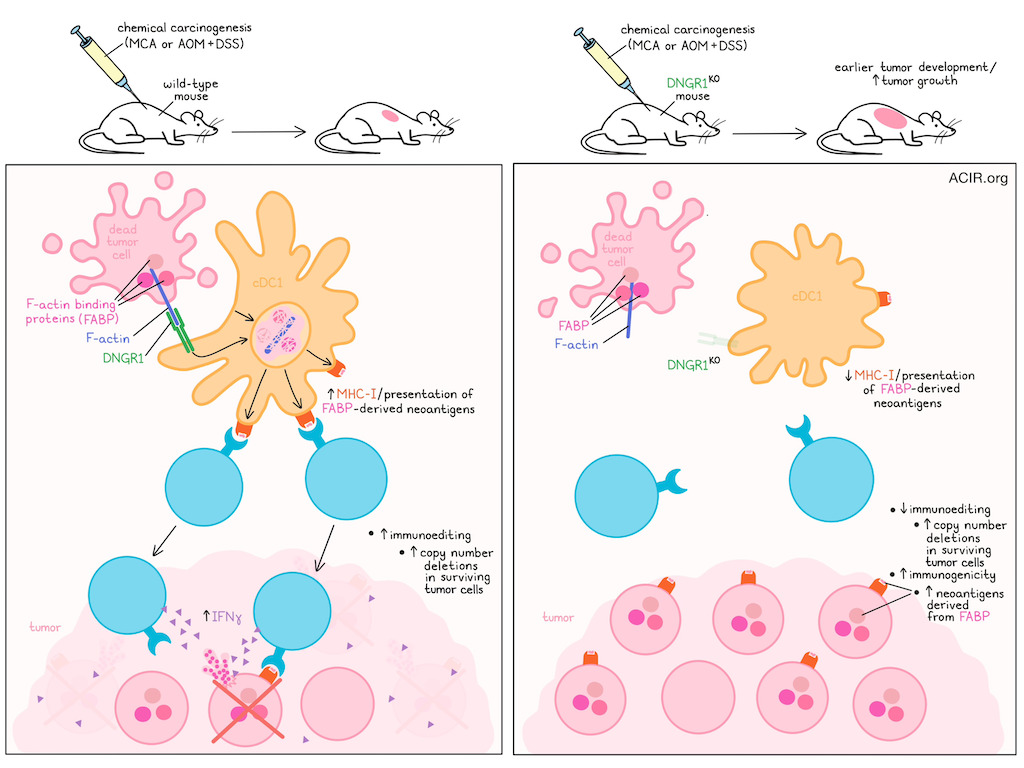

Type 1 conventional dendritic cells (cDC1s) cross-present tumor antigens to prime CD8+ T cells. DNGR-1 on cDC1s binds to F-actin of dead cells to allow for detection and internalization of necrotic debris, and signaling results in MHC-I processing and presentation of antigens from the dead cells. In a recent publication in Nature Immunology, Lim, Schulz et al. used chemical carcinogenesis models to investigate DNGR-1 functioning and how cross-presentation impacts immunoediting and the immunogenicity of tumors.

The researchers hypothesized that in chemical carcinogenesis mouse models, cell death and selection occur over a longer period of time than transplantable tumors, making it more likely to engage DNGR-1-dependent immunity. To assess this, C57BL/6 WT, DNGR-1KO, RAG1KO, and BATF3KO mice were challenged with the carcinogen 3-methylcholanthrene (MCA) and monitored for tumor development. The DNGR-1KO mice developed tumors earlier (median 95 days) than WT (113 days), in a similar way as observed in RAG1KO (lacking T and B cells) and BATF3KO (lacking cDC1s). Further, in a two-step model for colorectal carcinogenesis using azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS), the DNGR-1KO mice had a higher tumor burden than WT mice.

Cell lines were generated from the MCA-induced fibrosarcomas, and these were transplanted into WT mice to assess their immunogenicity. The cell lines derived from DNGR-1KO mice were controlled and/or rejected in 67% of cases, whereas only 42% of those from WT mice were rejected, suggesting that the DNGR-1KO-derived lines were more immunogenic.

To determine how DNGR-1 impacts the tumor mutational landscape, whole-exome sequencing was performed on cell lines from WT and KO mice. No major differences were detected between the mice in terms of overall tumor mutational burden or mutation types. There was, however, a significantly higher burden of copy number deletions in the WT-generated cell lines compared to the RAG1KO and DNGR-1KO.

To analyze immunoediting at the level of the mutational landscape, the researchers extracted all putative strong neoantigens from the cell lines using pVACtools to predict high-affinity mutant peptides. This did not reveal differences in the prevalence of strong neoantigens between cell lines. However, based on their prior work, they assessed neoantigens derived from F-actin-binding proteins (FABP). Predicted FABP neoantigens in tumors obtained from DNGR-1KO or RAG1KO mice were enriched compared to WT. Neoantigens derived from another cytoskeletal component, microtubule binding proteins (MBP), were not different between the cell lines.

Looking further into the individual FABP neoantigens detected, 22 genes with mutations predicted to generate strong neoantigens were identified across multiple cell lines. Of these, 13 peptides detected in the DNGR-1KO lines were synthesized, and 9/13 peptides bound to either H-2Kb or H-2Db on MHC-I. To assess the immunogenicity of these peptides, mice were immunized with antigen-presenting cells pulsed individually with each of these 9 peptides. Restimulation of splenocytes from these mice with the peptides yielded positive responses to 2/9 peptides, suggesting these were indeed immunogenic.

One of the lines from a DNGR-1KO host had two independent predicted strong neoantigens derived from mutations in a single FABP gene, Sptb, which encodes spectrin-β. Previous work from Bob Schreiber’s group has shown that mutated spectrin-β2 is a rejection neoantigen that undergoes immunoediting in MCA-induced primary tumors in Rag2-/- mice. The researchers generated MCA205 fibrosarcoma cell lines with high or low levels of WT or mutant spectrin-β2 and injected these into WT or sGSNKO mice. Gelsolin (encoded by the GSN gene), is a natural inhibitor of F-Actin:DNGR-1 interaction, so knockouts of GSN have enhanced DNGR-1 triggering. Tumors with high expression of the mutant spectrin-β2 were controlled similarly in both mice. Those with low expression of the mutant were better controlled in sGSNKO mice, which was dependent on DNGR-1. These data suggest that DNGR-1 signaling improves the visibility of tumors with low FABP neoantigen expression.

The researchers then hypothesized that antigen association with F-actin in dying cells increases the efficiency of cross-presentation of these antigens by cDC1s. To test this, they fused a His-tagged non-secreted version of OVA with either the actin-binding peptide LifeAct (LA) or a mutated version of LA (mutLA) that cannot bind F-actin. These constructs were transfected into HeLa cells, and cell death was induced using UV irradiation. These necrotic cells were fed to immortalized mouse splenic cDC1s (Mutu DCs), and cross-presentation was assessed by measuring IFNγ production after coculture with OVA-specific OT-I T cells. In this model, LA-OVA was more efficiently cross-presented than mutLA-OVA, and the cross-presentation of LA-OVA dead cells could be completely blocked with a DNGR-1-blocking antibody. Mutu DCs expressing a mutant DNGR-1 that cannot bind F-actin could cross-present soluble cell-free OVA, but could not cross-present LA-OVA dead cells. Cross-presentation of dead cells with mutLA-OVA was much lower than LA-OVA, but was DNGR-1-dependent. To ensure these results were not unique to LA-mediated anchoring, the experiments were also conducted with dead HeLa cells expressing F-actin-affimer-linked OVA (Aff-OVA). These cells were better substrates for cross-presentation than dead cells expressing OVA fused to a control affirmer.

Finally, the researchers immunized mice with dead HeLa cells expressing LA-OVA or mutLA-OVA mixed with the adjuvant poly I:C. In mice immunized with the cells expressing LA-OVA, there was increased expansion of endogenous OVA-specific CD8+ T cells and of IFNγ+ effector CD8+ T cells stimulated by peptide and monitored by intracellular staining. This difference in cross-presentation was further enhanced in mice lacking sGSN.

These data suggest that dead cell-associated antigens anchored to F-actin are efficiently cross-presented to CD8+ T cells by cDC1 in a DNGR-1-dependent manner. Loss of this DNGR-1-mediated cross-presentation limits the priming of FABP neoantigen-specific T cells. This process affects immunoediting by selecting tumor cells that have lost mutated FABP epitopes. These findings provide new insights into the immunoediting stage of tumor development, and may be important for studies assessing immune responses to cell-associated antigens, as well as for efforts to improve cDC1-mediated antitumor immunity.

Write-up by Maarje Wouters, image by Lauren Hitchings