Aiming to increase the number of patients, particularly pediatric patients, who respond to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), Shekarian et al. explored whether existing anti-infectious disease vaccines could be used to increase the immunogenicity of tumors and overcome resistance to ICB. The results, recently published in Science Translational Medicine, suggest that the clinical-grade rotavirus vaccines possess both immunostimulatory and oncolytic functions, and could potentially be quickly translated to the clinic in the context of cancer immunotherapy.

The researchers chose to pursue anti-infectious disease vaccines because they contain pathogens that trigger pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) – including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) – and could act as PRR agonists to prime an immune response. Evaluation of 14 viral and bacterial vaccines via incubation with transgenic HEK-293T cell lines expressing different TLRs revealed that the Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine (BCG) activated TLR2 and the typhoid fever vaccine (Tyavax) activated TLR4, as indicated by NF-κB induction. Surprisingly, the two rotavirus vaccines (Rotarix and Rotateq), when administered at mid-range concentrations, activated NF-κB in all transgenic cell lines, including the parental 293T cell line that did not express any TLRs, suggesting that the activation was independent of any TLR. At high concentrations, rotavirus vaccines reduced the viability of the 293T cells.

Next, the researchers evaluated in vivo antitumor properties of the four NF-κB-activating vaccines in a mouse model of neuroblastoma (Neuro2a) that is resistant to ICB monotherapies (anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, anti-CTLA-4) and their combinations. Intratumoral injections of Tyavax and BCG did not lead to any antitumor activity. In contrast, intratumoral injections of rotavirus vaccines led to tumor rejection in 40% of mice and a significant survival benefit. In mice with A20 B cell lymphoma, rotavirus led to tumor regressions in 70% of mice and complete cures in more than 50% of mice. In the NXS2 neuroblastoma model, rotavirus slowed tumor growth in some mice but did not significantly impact survival.

Exploring the mechanism behind the rotavirus-induced antitumor response, Shekarian et al. observed that in vitro, the rotavirus vaccines were cytotoxic against numerous human and mouse cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (albeit less potently in mice), and were preferentially cytotoxic against cancer cells versus healthy cells, suggesting that the rotavirus was an oncolytic virus. When the rotavirus was inactivated with heat and UV irradiation, cytotoxicity was lost in vitro. Transcriptomic analysis of various tumor cell types exposed in vitro to active or inactivated rotavirus revealed six commonly upregulated genes, including interferon regulatory factor 7 (Irf7), CD274 (encoding PD-L1), and Ddx58 (encoding the double-stranded RNA sensor retinoic acid-inducible gene I, RIG-I). Notably, rotavirus also activated human monocyte-derived macrophages from healthy donors, even when the rotavirus was inactivated.

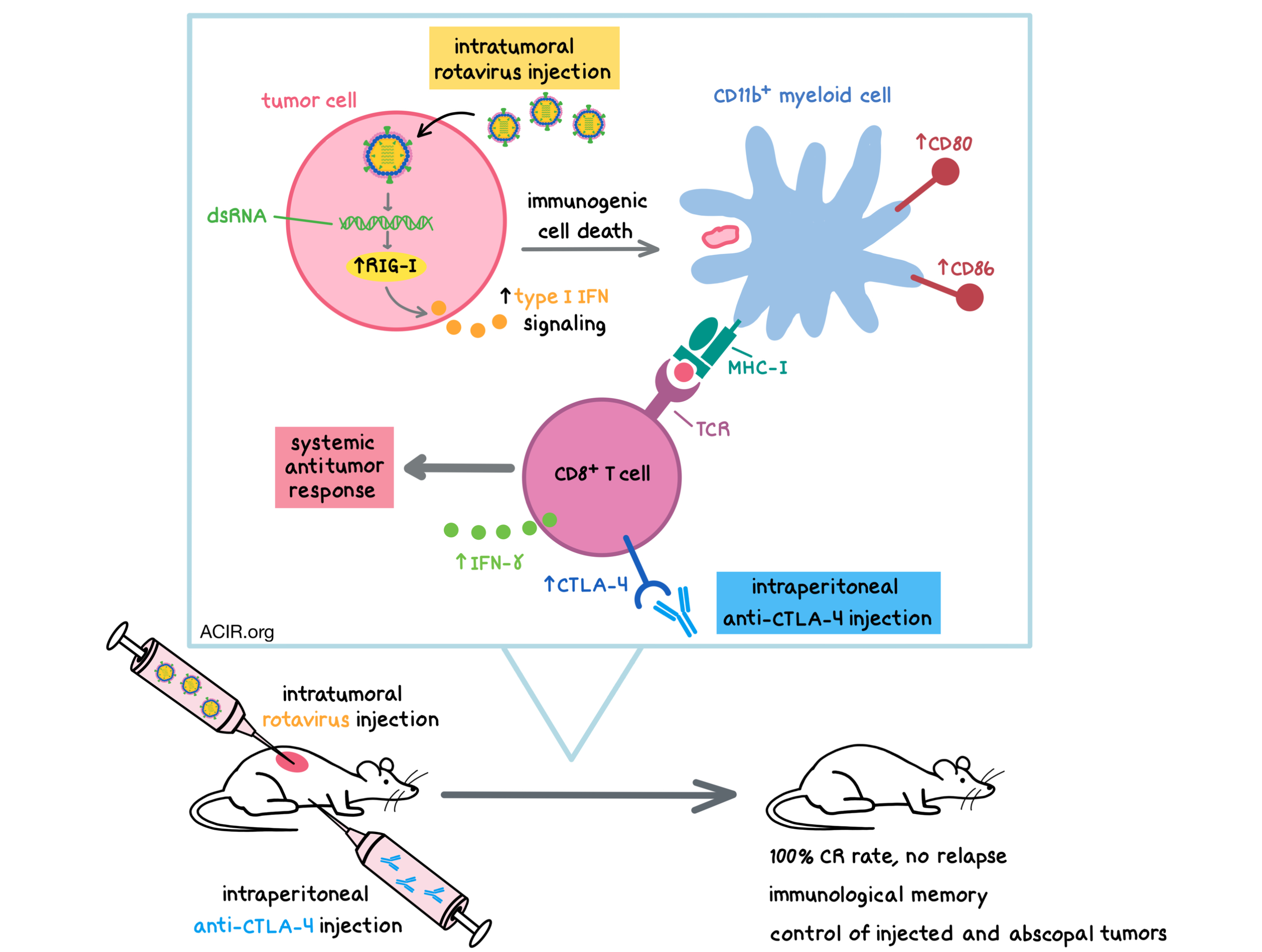

In vivo, as early as 24 hours after intratumoral injection, rotavirus treatment led to a rapid increase in the percentage of intratumoral CD11b+ myeloid cells, but did not affect the proportions of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, or Tregs. Active, but not inactivated, rotavirus upregulated the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 in murine tumors, particularly on myeloid cells. A significant proportion of CD8+ T cells also had upregulated activation markers. CTLA-4 was upregulated on CD8+ T cells and Tregs. Rotavirus also induced immunogenic cell death in human and murine cancer cell lines, as indicated by the extracellular release of ATP. Genes commonly upregulated in vivo by both active and inactive rotavirus included type I IFN pathway genes, Ifng, T effector genes (e.g. IL-25, IL-9, IL-17, Tbet), and retinoic acid binding-related orphan receptor c (RORc). Together, the in vitro and in vivo data show that the rotavirus, whether active or inactivated, triggers a coordinated antitumor immune response.

Mechanistic data provided the rationale for testing intratumoral injection of rotavirus in combination with systemic anti-CTLA-4. In the Neuro2a model, which was resistant to anti-CTLA-4 and partially responsive to rotavirus, the combination treatment synergized to achieve a 100% complete response rate with no relapse. Similar efficacy was observed in the A20, EMT6, and CT26 (colon carcinoma) tumor models. Importantly, intratumoral delivery of rotavirus was required for the synergistic effect, as systemic delivery had very little antitumor effect, both alone and in combination with anti-CTLA-4. Since rotavirus led to upregulation of PD-L1 on cancer cells, the researchers also tested the combination of intratumoral injection of the rotavirus and systemic injection of anti-PD-L1 and found that it resulted in a 100% cure rate in the A20 tumor model.

Next, the researchers asked whether the rotavirus-mediated antitumor responses were primarily due to direct oncolytic or immune-mediated effects. In the immunodeficient NSG mice bearing Neuro2a tumors, the rotavirus-mediated antitumor response was completely abolished. Surprisingly, while the inactivated rotavirus elicited no antitumor response in wild-type mice as a monotherapy, it synergized with and overcame resistance to anti-CTLA-4 with a similar efficacy to the active rotavirus. Depletion experiments demonstrated that CD8+ T cells were absolutely required for the antitumor effect of rotavirus monotherapy and combination with anti-CTLA-4. CD4+ T cells and NK cells also contributed to the antitumor response. CD8+ T cells had upregulated IFNγ production and upregulated surface activation markers (e.g. CD137, OX40) after combination treatment. The combination therapy induced a systemic antitumor response and led to the formation of long-term, tumor-specific immunological memory in cured mice and the ability to control both injected and abscopal tumors. Furthermore, preimmunization with the rotavirus vaccine did not impact the synergistic antitumor effect of the combination therapy in mice. Thus, although direct oncolytic effects could be present, rotavirus-mediated antitumor effect involved the engagement of various immune cells.

Altogether, Shekarian et al. demonstrated that rotavirus vaccines synergized with and overcame resistance to anti-CTLA-4 in several cancer models, including those common in pediatric patients. As rotavirus vaccines are clinically used in pediatric patients, they could potentially be quickly translated to the clinic as a source of an oncolytic virus and tested in combination with approved checkpoint blockade immunotherapies.

by Anna Scherer

Meet the Researcher

This week, Aurélien Marabelle answered our questions.

What prompted you to tackle this research question?

During my postdoc in Prof Ronald Levy’ lab at Stanford University, we showed that synthetic TLR9 agonists injected into mouse lymphoma tumors could overcome the resistance to immune checkpoint targeted antibodies. Back from my post doc in 2012, I wanted to find clinical grade pattern recognition (PRR) agonists that I could eventually translate to the clinic for the intratumoral treatment of pediatric cancers (I’m a pediatric oncologist by training). The idea at the beginning was to check if commercially available anti-infectious vaccines, which are full of pathogen extracts, could behave as PRR agonists and could have therapeutic value, notably in murine models of pediatric tumors.

What was the most surprising finding of this study for you?

We had several surprises along the way, such as the oncolytic properties of rotavirus and their ability to overcome anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 resistance upon intratumoral injections. But what was really unexpected was that although the heat and UV inactivated rotavirus lost its oncolytic properties, it maintained its synergy with immune checkpoint targeted therapies (through RIG-I stimulation).

What was the coolest thing you’ve learned (about) recently outside of the lab?

The synergy and abscopal responses in patients of the intratumoral combination of FLT3L with TLR3 agonist and low dose irradiation [1].

1. Hammerich L, Marron TU, Upadhyay R, Svensson-Arvelund J, Dhainaut M, Hussein S, et al. Systemic clinical tumor regressions and potentiation of PD1 blockade with in situ vaccination. Nat Med. 2019.