Immune cells shift shapes as they travel through the body’s tissues. Shape-sensing pathways play a role in adapting to these deformations, but it remains unknown how shape sensing affects immune function. Alraies et al. recently published data in Nature Immunology on changes to the immune function of dendritic cells (DCs) while undergoing cell shape changes.

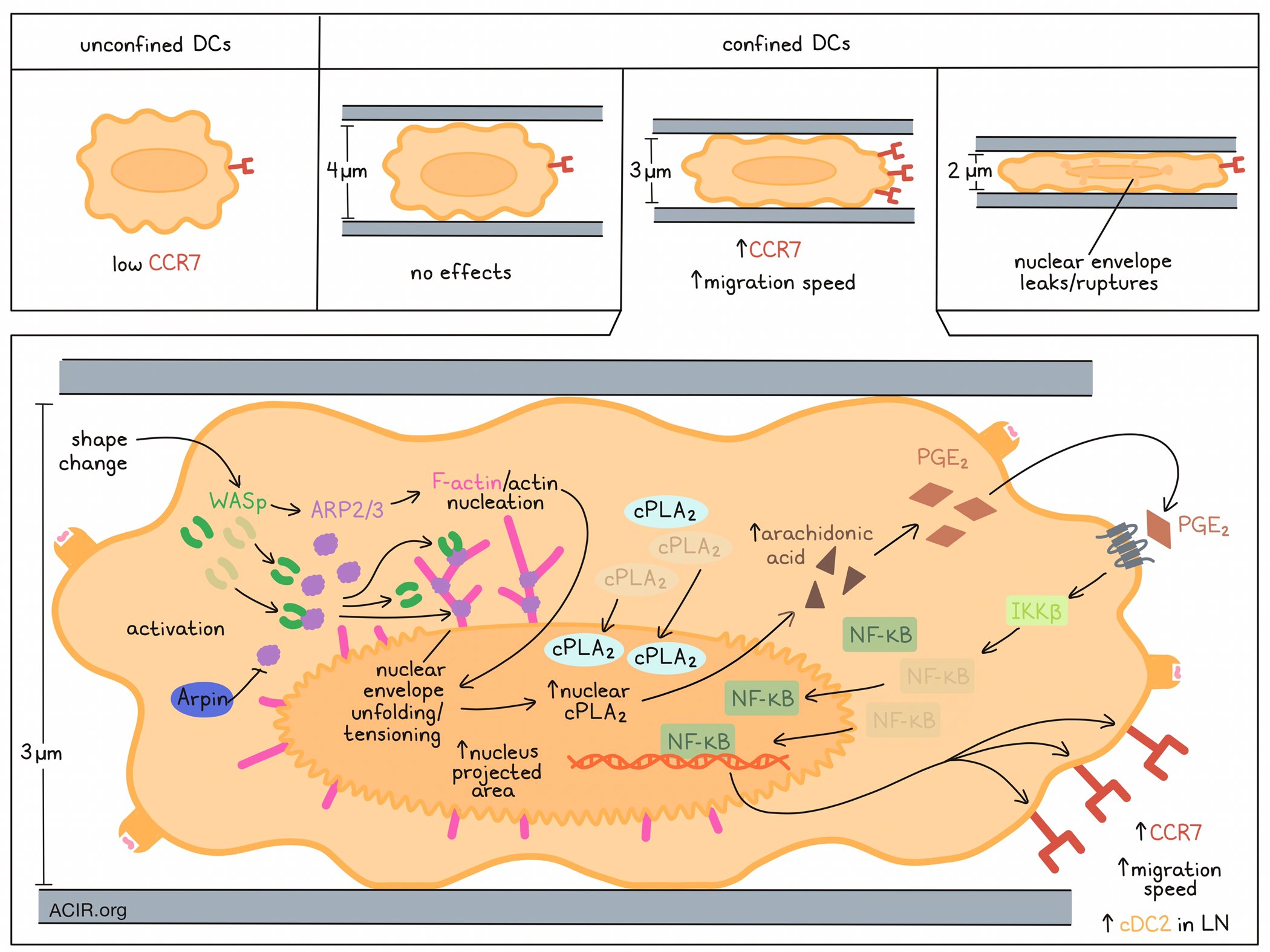

DCs require CCR7 expression and changes to their motility to allow trafficking to lymph nodes (LN). Previously, these researchers showed that DC motility was increased by confinement-induced stretching of the nuclear envelope, which promoted actomyosin contractility; this effect was dependent on the lipid metabolism enzyme cPLA2. Alraies et al. hypothesized that a shape change might increase CCR7 expression to help the DCs reach their destination. To test this hypothesis, in vitro experiments were conducted in which unstimulated bone marrow-derived immature DC cell shapes were manipulated using a cell-confining device. While the unconfined DCs expressed low levels of CCR7, CCR7 increased, along with their migration speed, when cells were confined at a height of 3 μm (but not 2 or 4 μm).

Since previous research had shown that cPLA2 increased cell motility upon nuclear deformation, the researchers then investigated whether cPLA2 activity was involved in the CCR7 upregulation. When the drug AACOCF3 was used to limit the activity of cPLA2 in an in vitro model, no CCR7 was upregulated on the DCs confined at 3 μm height. This was also true for Pla2g4a-knockdown or -knockout DCs, which also had no increased cell motility. However, cPLA2-deficient cells still upregulated CCR7 in response to LPS exposure, suggesting that the activity of cPLA2 on CCR7 expression only applies in the setting of cell shape changes. cPLA2 accumulated in the nucleus of DCs confined at 3 μm height, but not in controls, and this enzyme is known to translocate to the nucleus and associate there with the inner nuclear membrane after activation. When the shape of the nucleus in the cells was analyzed after confinement at different heights, those at a height of 3 and 2 μm had an increased nucleus-projected area. However, DCs confined at 2 μm demonstrated leakage of nuclear localization signal-tagged GFP into the cytoplasm, indicative of nuclear envelope rupture occurring at this height, suggesting an intact nuclear envelope and nuclear localization of cPLA2 is required for these confinement-induced effects.

The researchers assessed whether nuclear translocation and activation were a result of simple passive stretching of the DC nucleus under confinement, or due to an active deformation process, which might be driven by ARP2/3. Live imaging analysis showed that in the 3 μm confined state, a cloud of perinuclear F-actin appears in the cells, and treatment with the ARP2/3 inhibitor CK666 removed this actin structure. Further, inhibitor treatment limited the upregulation of CCR7 and nuclear accumulation of cPLA2 after confinement. These effects were also observed in DCs that lacked Wiscott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp), which activates ARP2/3. The researchers also discovered that the ARP2/3-dependent actin nucleation resulted in unfolding and tensioning of the nuclear envelope in response to confinement, which were essential to induce the CCR7 expression increase.

Alraies et al. then assessed the physiological relevance of shape sensing by ARP2/3 and cPLA2 by testing cPLA2, WASp, and Arpin (encoding a physiologic ARP2/3 inhibitor) knockouts, and assessing whether these induced changes in the number of migratory DCs in skin-draining LNs at steady-state (no inflammation). Previously, it has been shown that at steady-state, cDC2s are more likely to migrate from the skin to the LN than cDC1s. In WASpko and cPLA2ko mice, consistent with the effects of these gene products on CCR7 expression, there were fewer migratory cDC2 in inguinal LN, while no differences were detected for cDC1, which were present in lower numbers. Arpinko mice, on the other hand, had higher frequencies of migratory cDC2s in LNs.

The researchers then investigated if the ARP2/3–cPLA2axis relies on IKKβ-dependent NF-κB activation, and whether that induces transcriptional reprogramming of the DCs. RNAseq analysis of DCs from the various knockouts showed that confined cPLA2wt and cPLA2ko cells did not cluster together, suggesting differences in gene expression profiles, while no differences were detected between those cells if they were non-confined. Most of the upregulated genes in the confined setting were dependent on cPLA2. Further, analysis of CK666-treated cells showed that genes upregulated in a cPLA2-dependent manner were also dependent on ARP2/3 activity. In confined DCs treated with the IKKβ inhibitor BI1605906 or in DCs lacking the Ikbkb gene, Ccr7 was not upregulated. NF-κB nuclear translocation was reduced in DCs lacking cPLA2, while IKKβ inhibition did not impact the nuclear translocation of cPLA2 in confined DCs. This suggests that cPLA2 may act upstream of IKKβ and NF-κB in triggering CCR7 expression. To assess whether the production of PGE2 from arachidonic acid (which is produced by cPLA2) contributes to the transcriptional reprogramming of confined DCs, PGE2 was added to confined cPLA2ko DCs. This resulted in increased CCR7 expression. This effect was dependent on PGE2- and IKKβ-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation.

The migration of DCs to LNs at steady state is important for the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. The researchers compared the transcriptomes of DCs with or without cPLA2 in the confined setting with DCs exposed to LPS. cPLA2 did not impact the gene expression profiles of DCs exposed to LPS. Further comparing the transcriptional profiles of confined and LPS-exposed DCs showed that the “regulation of helper T cell differentiation” pathway was induced by LPS only. To test whether the confined DCs were less potent in activating T cells than the LPS-treated DCs, the DCs were loaded with the class II OVA peptide and incubated with OT-II T cells. There was less T cell activation and proliferation induced by confined DCs than the LPS-treated DCs. In confined DCs, there was more activation of IRF1-, STAT1-, STAT3-, and STAT5A-dependent transcription factors, which are involved in IFN signaling and/or activation of NF-κB.

Therefore, these data suggest that interactions between the cytoskeleton and cPLA2 reprogram DCs when undergoing shape changes when traveling through tissues. These interactions allow DCs to traffic to the LN in an immunoregulatory state, important for the maintenance of tolerance.

Write-up by Maartje Wouters, image by Lauren Hitchings.