The antitumor efficacy of cancer immunotherapy often relies heavily on CD8+ and CD4+ T cell recognition of tumor antigens presented on MHC molecules. However, investigating settings with low or no tumor MHC expression, Kim and Haerr et al. found that the combination of agonistic anti-CD40 and dual immune checkpoint blockade (ICB; anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4) was still effective against multiple pancreatic tumor models that were deficient in MHC-I, MHC-II, and IFNγR. Results from their investigation into the mechanism underlying the efficacy of this immunotherapy were recently published in Cancer Immunology Research.

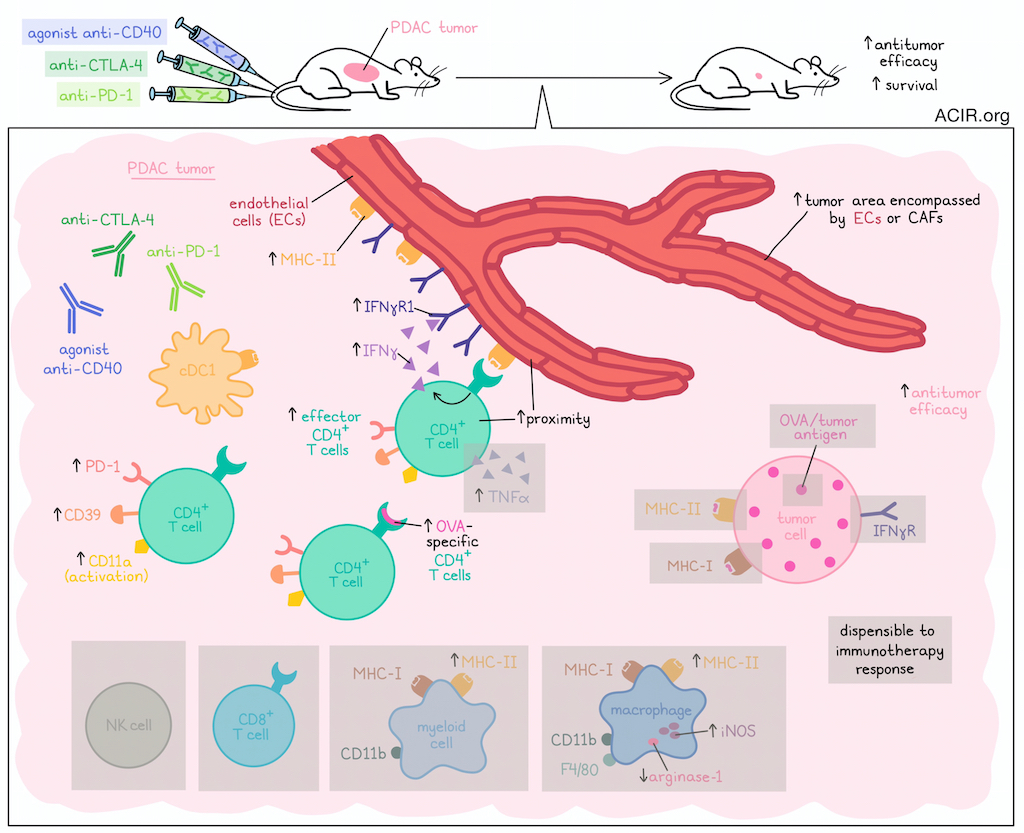

Initially, Kim and Haerr et al. evaluated the V6 clonal PDAC cell line engineered to express OVA, which was presented as peptides on MHC-I (H-2Kb allele) and MHC-II (I-Ab allele). V6 tumor cells were spontaneously rejected upon implantation into wild-type mice, and ablation of H-2Kb on V6 cells (generating the V6K line) allowed for progressive tumor growth, as expected. However, V6K tumors could be controlled upon treatment with the combination of agonistic anti-CD40 and ICB (dual anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4), and mice were protected from rechallenge. CD4+ T cells and cDC1s, but not CD8+ T cells or NK cells, were found to be required for this antitumor efficacy.

Investigating whether the response to agonistic anti-CD40/ICB could be attributed to expression of OVA or Cas9 (used to engineer the expression of OVA), the researchers showed that mice cured of V6K tumors also rejected parental MD11.2 PDAC tumors, which lacked OVA or Cas9 expression, and that this response was dependent on CD4+ T cell. Anti-CD40/ICB also remained effective against V6K tumors in Act-mOVA mice, which are centrally tolerant to OVA, and against a non-OVA-expressing PDAC tumor clone in which MHC-I was ablated. These results suggested that while treatment efficacy was dependent on CD4+ T cells, it was not dependent on recognition of a strong foreign antigen.

To characterize the phenotype and function of CD4+ T cells involved in the response to anti-CD40/ICB, the researchers analyzed tumors 10 days after start of treatment, and found increases in the proportion and absolute counts of activated (CD11a+) CD4+ effector T cells, CD4+ effector T cells expressing PD-1 and CD39, and CD4+ cells specific for OVA peptides presented on the I-Ab MHC-II allele. Meanwhile, proportions of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells were similar between treated and control mice, underscoring the role of CD4+ T cells over CD8+ T cells in this setting.

To determine whether CD4+ T cells mediated antitumor immunity through cytotoxic functions, the researchers used flow cytometry to characterize expression of granzyme A, granzyme B, and CD107a (degranulation), and found that treatment with anti-CD40/ICB increased the absolute cell counts, but not the proportions of CD4+ T cells expressing each of the cytotoxic molecules. Perforin was also not required for antitumor efficacy (based on experiments in perforin-KO mice), and expression of death ligands including NKG2D, Fas ligand, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) on CD4+ T cells did not significantly influence treatment. Together these results suggested that classical cytotoxic functions were not the main mechanism by which CD4+ T cells exerted antitumor immunity in response to anti-CD40/ICB.

Next, assessing CD4+ T cell production of the important immune modulators IFNγ and TNFα, the researchers found that anti-CD40/ICB led to upregulation of both molecules. While the efficacy of treatment was maintained in models lacking expression of TNFα or TNFα receptor (TNF-αR), a global lack of IFNγ or the IFNγR in host mice abrogated treatment efficacy. Interestingly, neither ablation of IFNγR expression nor ablation of I-Ab expression in tumor cell lines abrogated their responses to anti-CD40/ICB, suggesting that tumor cells themselves are not the direct targets of TCR/MHC-II interactions or IFNγ.

To identify potential interaction partners of CD4+ T cells, the researchers assessed other MHC-II-expressing cells within the TME, starting with myeloid cell subsets. While total myeloid cells and cDC1s expressing MHC-II remained the same after anti-CD40/ICB, the proportion of tumor-associated macrophages expressing MHC-II increased upon treatment. There were no significant changes in their presentation of OVA peptides on MHC-I by any cell subsets, but I-Ab (MHC-II) expression was specifically increased on subsets of CD11b+ myeloid cell and F4/80+CD11b+ macrophage subsets that were also presenting OVA peptides on MHC-I.

Investigating whether any of the intratumoral myeloid cell types they identified could potentially eliminate tumor cells in response to CD4+ T cells, the researchers found that while inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which can induce tumor cell death, was increased in intramural macrophages after treatment, and arginase-1 (an immunosuppressive molecule) was reduced, both iNOS expression and macrophages were ultimately dispensable to antitumor efficacy.

Moving on to other cell types, the researchers utilized a publicly available scRNAseq dataset of 41,986 cells from 24 human PDAC samples. Analysis revealed that macrophages and ECs, along with some CAFs and ductal cells, were the main cells expressing IFNGR1, while IFNGR2 was more ubiquitously expressed. Expression of most MHC-II locus genes were mainly restricted to endothelial cells (ECs), macrophages, and B cells. Exploring the possibility that ECs might play a role in the antitumor efficacy of anti-CD40/ICB, the researchers returned to the V6K tumor model in mice and found that while treatment induced no changes in the proportions of IFNγR1+ ECs or CAFs, it did strongly increase expression levels of IFNγR1 on individual ECs. Treatment also increased the proportions of ECs expressing I-Ab and levels of I-Ab on individual ECs. Further, CD4+ T cells and ECs were closer in proximity following treatment, suggesting potential interactions. Finally, the researchers showed that anti-CD4 depleting antibodies significantly reduced the proportions and magnitude of I-Ab on blood vessels within the TME, further supporting the influence of CD4+ T cells on endothelial cells. In slightly longer-term studies, the researchers found that the area of the tumor encompassed by either ECs or CAFs was increased after treatment.

Overall, these results from Kim and Haerr et al. suggest that even in the absence of MHC-I or MHC-II or in tumors lacking foreign antigens, anti-CD40/ICB may still induce antitumor efficacy by activating effector CD4+ T cells that produce IFNγ and remodel the tumor stroma. Further investigation into the cross-talk between these cell types could reveal additional mechanisms that could potentially be targeted to improve cancer immunotherapy in antigen escape settings.

Write-up and image by Lauren Hitchings